Eamonn O’Reilly on the narrow path to our climate targets

Ireland has mountains(plural) to climb.

Eamonn O’Reilly is a man accustomed to thinking carefully about big projects. He was the chief executive of Dublin Port for 12 years, finishing up in 2022. In that time he oversaw more than €500 million of capital investment.

Today, O’Reilly serves as chairman of the Energy and Climate Action Committee at the Irish Academy of Engineering (IAE). The IAE provides expert advice to policymakers around technical engineering matters.

O’Reilly is the lead author of a new IAE report. The report sets out, in specific detail, the scale of investment Ireland will need to undertake in order to hit its 2050 decarbonisation targets.

It won’t surprise many to hear Ireland is struggling to meet its decarbonisation targets. What is shocking is the breadth of the problem, as laid out in the report. Ireland has to solve huge problems in six energy-related domains simultaneously: onshore wind, offshore wind, transmission, gas turbines, gas supply, and battery storage. It needs to mobilise resources to solve these problems at the same time as every other rich country needs them.

What follows is lightly edited for clarity.

Seán Keyes: Why write this report?

Eamonn O’Reilly: The concern from the Academy’s point of view is that we are walking into areas of uncertainty which, in previous decades, would have been unimaginable. What I have in mind is the reliability of the national electricity supply. In the past it would have been unheard-of, if there were significant worries, that we might not have generating capacity to meet demand. That is one area: reliability.

The second area is security of supply. There is great concern in the Academy at how lackadaisical Ireland has been in addressing a well-understood challenge that the country has about the security of our energy supplies in general and, by extension, the security of our electricity supplies. These concerns have been known since the oil shocks in the 1970s. If you go back to 1990, we had a relatively secure electricity supply because we had a great big yard full of coal at Moneypoint capable of putting out 900 MW to a market where the maximum demand, was about 2,000 MW. We also had indigenous gas in large quantities and we were digging up the Midlands to burn peat. Taking those three together, we were pretty secure in 1990 as regards the electricity system.

We are now entering an era when security of supply is at risk. The frustrating thing is that this was recognised by the Government as long ago as 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea. It was recognised that there could be an energy-security threat for geopolitical reasons—that was in 2014—and in 2024 there is a very well-written section on risk to energy in the National Risk Assessment, which is published annually. The purpose of our report is to bring together the two topics of reliability and security in the context of the energy transition. The green transition exacerbates the scale of those challenges because of the intermittency of renewables.

Seán Keyes: In your report you set out a realistic path forward for Ireland, based on existing technologies that are proven and that have some minimum financial viability. Do you want to sketch out what that energy mix looks like?

Eamonn O’Reilly: The starting point is the policy needed to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from the electricity sector. We have tried to identify the scale of projects that must be completed with the technologies available to us, and we come up with about 350 projects, including fixed-bottom and onshore wind, solar, interconnectors, new overhead transmission lines, and storage. Taken together, 3at .

There is an absence of a clear plan as to what we are going to do and, by extension, what we can realistically achieve by 2050. That’s what we are clear about.

Seán Keyes: Your plan involves a mix of renewables, interconnectors and storage –but also the use of natural gas for resilience when the renewable system is not working.

Eamonn O’Reilly: I wouldn’t even refer to it as our plan; this is simply where policy is taking us.

We tried to bring together the scale of it — what it looks like in project-delivery terms. From the engineers’ perspective, we have identified about 350 projects in just 25 years.

We discuss energy reliability and security. We do not see any other option, for times when wind and solar are insufficient, but fossil fuels — specifically natural gas. That is inescapable. It is ironic that, as we reduce our dependence on natural gas and other fossil fuels in energy terms, we will actually need to increase gas generation capacity. The reason is simple: if everyone installs a heat pump, replaces gas or oil boilers and moves to electric cars, electricity demand will rise.

We put annual demand at 80 TWh by 2050, based on average EirGrid scenarios; 80 compares with 34 TWh in 2024. Any business whose output grows from 34 to 80 in that period faces a major investment challenge. Peak power is going to rise too: it has already touched about 6,000 MW and could reach something like 12,000 MW by 2050.

Seán Keyes: You cited a number of 352 energy infrastructure projects that would be required by 2050. 352 infrastructure projects won’t mean anything to most people. Is that big, or small? How does it compare with what we’ve been building, and how much will we have to build each year?

Eamonn O’Reilly: The report inevitably has a lot of numbers in it. That is one of the challenges of talking about the energy transition: you cannot understand it without looking at the numbers. So the report is dense in numbers and we can’t get away from that. For example, onshore wind: Ireland has just under 5,000 MW today, and Government policy is to reach 9,000 MW by 2030. That means each year we need to bring online more additional wind-power capacity than we have ever brought forward in a single year to date.

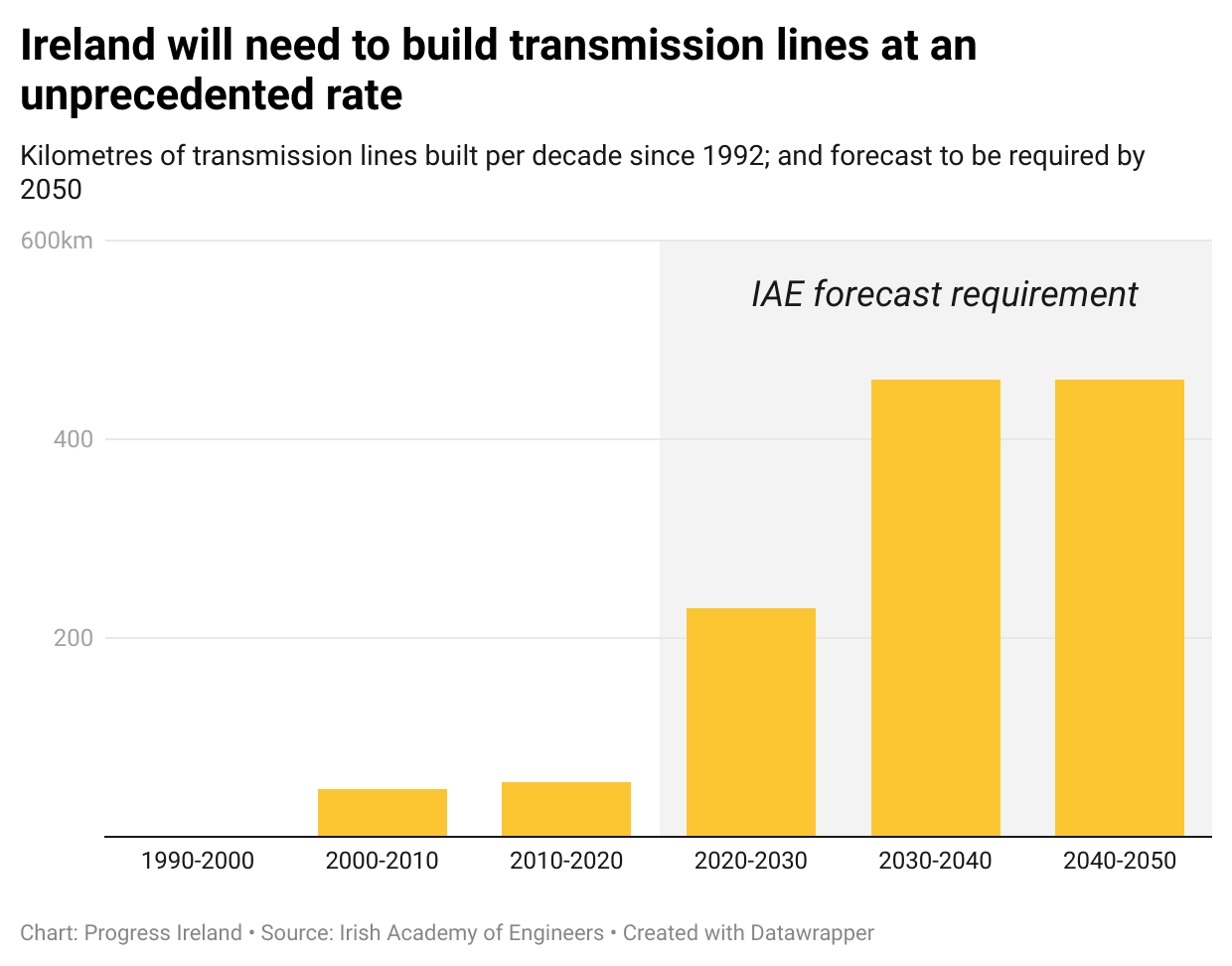

For the transmission grid, we relied on EirGrid’s “Grid 25”, which looked at the hundreds of kilometres of 400 kV and 220 kV overhead lines required. We have not built a single new line in more than a decade, and none is in EirGrid’s current ten-year Transmission Development Plan. You cannot move 80 TWh at up to 12,000 MW using only the existing grid, whether using additional overhead lines (the vast majority) or underground cables. Everybody agrees we need more infrastructure, yet we have no project underway except the North–South Interconnector, and by the time that is built it will have taken about 30 years.

Seán Keyes: That makes it tangible: one project is stuck in planning hell for 25 years, and we need roughly 40-odd (though not of that scale) by 2050.

Eamonn O’Reilly: We also need multiple onshore wind farms. We already have a lot of onshore wind — comparable to Denmark today. If we hit 9,000 MW, we will have far more onshore wind capacity per million people or per 100 km² than Denmark has.

The report says energy policy contains too much wishful thinking; it hasn’t taken the next step into what is realistic and what it involves. What it involves is a lot of projects that many people won’t want to see. If the Government states, “This is what we are going to do,” but doesn’t explain and support implementation, the outlook for net-zero is bleak.

Seán Keyes: If you could click your fingers and have all this infrastructure appear overnight, how would the country look and feel?

Eamonn O’Reilly: If you drive around Ireland you will see far more transmission lines — no question. In Britain you see many more lines because of its industrial base. I don’t think Ireland will look like Britain’s industrial heartlands, but you will definitely see more lines. Travel outside Copenhagen and you see wind turbines everywhere; I think that will be a feature in Ireland. Offshore wind farms won’t be everywhere — they will be concentrated in small areas. The Dublin Array project, for instance, would be visible from Dún Laoghaire: small turbines on the horizon, like the Father Ted joke—“small, far away.” I don’t see that fundamentally changing our lives, though others might take a different view.

Policy must be specific. We need planning applications that can’t be rejected on policy grounds — only on environmental grounds where justified. If projects fail on policy grounds, either developers are doing something wrong or policy has led them up the garden path; I think it’s the latter.

Seán Keyes: What about those who insist transmission lines should be buried?

Eamonn O’Reilly: The issue has been thrashed around for decades — electromagnetic fields, visual impact, and so on. Put cables underground and the useful capacity per kilometre drops for technical reasons; overhead lines are also cheaper and faults easier to find. The only good reason to bury lines is to hide them, or, in a city, because you can’t run overhead lines through streets. ESB, EirGrid and ESB Networks have generally got the balance right: bury short stretches where necessary; build 400 kV overhead lines for long-distance transmission, as from Moneypoint to the east coast.

Seán Keyes: Transmission is politically hard, but so is gas infrastructure. What gas investments will we have to make in floating regasification, offshore fields, and new gas turbines?

Eamonn O’Reilly: We need far more renewables, yet renewables alone never get you over the line. The report shows that in 2024, for about 2,100 hours (roughly 88 days), almost 5,000 MW of wind generated less than 500 MW. Intermittency means you need back-up power of last resort. The more renewables, the less you run the gas turbines, but nobody will thank the government if blackouts occur. So we need more gas turbines.

Gas needs a new narrative.

That raises energy security. The 2024 Government risk assessment is right: we rely on two parallel gas pipes from Scotland. We need diversity. LNG is the obvious route, perhaps supplemented by further exploration — Corrib, for example. A large LNG plant at Ballylongford/Shannon Estuary had permission in 2008 but never went ahead. A later proposal was refused because of anti-fracking policy; the High Court is involved.

The government now talks about an FSRU—a floating storage and regasification unit. It wants something small, leased, “not to affect the market”. Bill Nicholson once said of football’s offside rule, “If you’re not interfering with play, you shouldn’t be on the pitch.” If an FSRU isn’t meant to affect the market, why have it?

The proposed capacities—1-2 TWh of storage—are too small. With peak demand at 12,000 MW, and 30 days of storage, you need about 13.2 TWh. Government has finally accepted the need for LNG, but it still has to decide whether it should be a floating unit or a large fixed facility like Milford Haven, Zeebrugge or Świnoujście.

Seán Keyes: You were very focused on proven technologies. You have, in the appendix, a few potential technologies that may come on-stream in the next 15 to 25 years. Which of those do you think has the greatest potential to be a big factor by 2050?

Eamonn O’Reilly: Just to clarify, while we focus on what is available today, that does not mean we should dismiss technologies that are not yet feasible. Work absolutely must continue on them. Take small-modular nuclear reactors: we have already issued a report saying Ireland should proceed on the basis that the technology will be proven and should build the institutional capacity to support a nuclear programme if that happens. Likewise, ESB and Shannon Foynes Port Company should— and, to be fair, I think they are—moving ahead with planning applications for port facilities in the Shannon Estuary to construct and service floating offshore wind. We would also encourage the hydrogen pilots ESB is running.

If you force me to pick between hydrogen, floating offshore wind and small-modular reactors, that is a leading question, but my guess is that somewhere between small-modular reactors and floating offshore wind we will find viable options. Floating offshore has clear obstacles—but that is where great entrepreneurs come in, and people with negative views (me, perhaps) get pushed aside while they simply get on and do it. Eddie O’Connor is a great example.

Still, there are real practical problems to solve before floating offshore works in Atlantic conditions. A recent UK auction—Allocation Round 6—set a strike price of roughly £140/MWh (2012 prices) for floating projects in Scotland. That is far above Hinkley Point C nuclear at ~£93/MWh and above the €86/MWh (2023 prices) for fixed-bottom offshore in Ireland. So although this may be the first big floating project completed in our region, starting at that price means a lot of cost-reduction work lies ahead if it is to compete with fixed-bottom or onshore wind.

For me, floating offshore carries a huge question-mark. It is telling that the Sceirde Rocks project—about 450 MW off Galway—may not proceed; site investigations suggest major difficulties, and that is comparatively shallow water. If the proven technology used for Kish Bank light house back in 1963 can't provide the solution for Sceirde Rocks in 2025, then the challenges for floating platforms in even rougher seas off the west coast are obvious..

Seán Keyes: Your report focuses on engineering; do you have a sense of the capital required by 2050?

Eamonn O’Reilly: We avoided that: we lack the data for a sound estimate. We do note that Ireland already has the highest electricity prices in Europe and faces a huge investment programme. Besides the 350 projects we identify, ESB Networks has many transmission and distribution projects. EirGrid lists 233 projects over the next ten years, many expanding substation capacity. A detailed study is needed on investment requirements and investor returns. ESB Networks and EirGrid have regulated tariffs approved by the CRU; those tariffs must be high enough to finance borrowing, and all of that is recovered from consumers. Offshore-wind developers work under contracts for difference— ORESS1 averaged €86.05 /MWh, indexed to inflation. Interconnector developers need cap-and-floor mechanisms to guarantee minimum returns. Everywhere you look you see cost recovery; real competition is impossible because the system has to work all the time and investors need certainty.

We are moving back to what existed pre-liberalisation, when ESB was a monopoly: essentially a cost-recovery system. A major piece of work is required to bring together all the disparate elements of capital investment and operating cost.

Seán Keyes: I saw a UK estimate that put decarbonisation at about £50,000 per household. Were that to hold in Ireland, we would need investment of multiple tens of billions in total.

Eamonn O’Reilly: Today’s figure for Ireland’s national debt is roughly €40,000 per head. Based on what we have seen, the energy-transition bill per person could be similar.

*****

The Irish Academy of Engineering’s full report on Ireland’s 2050 targets can be downloaded here.