From Tokyo to Dublin: The Land Readjustment Playbook Ireland Needs

How Japan builds its dense cities

Japan is famous for its urban areas. Its world class transport network makes travel easy and efficient, and there are dense urban areas around its stations. This transit-oriented development supports public transport, increases walkability, and creates larger labour markets, among other benefits. In other words, it’s environmentally sustainable, healthy, and economically beneficial.

By contrast, Ireland struggles to create dense urban zones. This process is sometimes called compact growth as more is built within already-existing towns and cities.

Doing compact growth right would address a lot of Ireland’s most pressing problems: it would increase the supply of housing where it’s most needed, putting a dent into the housing crisis. It would reduce our dependence on cars, enabling mass transit systems like the metro, especially in Dublin. And it would make our cities more liveable and economically attractive, bolstering our competitiveness at a time when the global investment environment is increasingly unstable.

Compact growth is difficult to achieve, however. Small plots of land might need to be combined to make a new project viable. For example, if you want to build an apartment block with a small park beside it, you can’t do that without the cooperation of all the people who currently own that land. Given Ireland’s fragmented land ownership system, that could easily be quite a lot of people to get onboard. A single holdout in the middle of your planned apartment complex could stop the project. How can the individual owners be persuaded to cooperate? And at what cost?

Given a fragmented land ownership system of its own, how does Japan deliver compact growth in its biggest cities?

Land readjustment

A large part of the answer is land readjustment. It’s a framework for pooling fragmented land parcels for joint development, with owners transferring a portion of their land for public use.

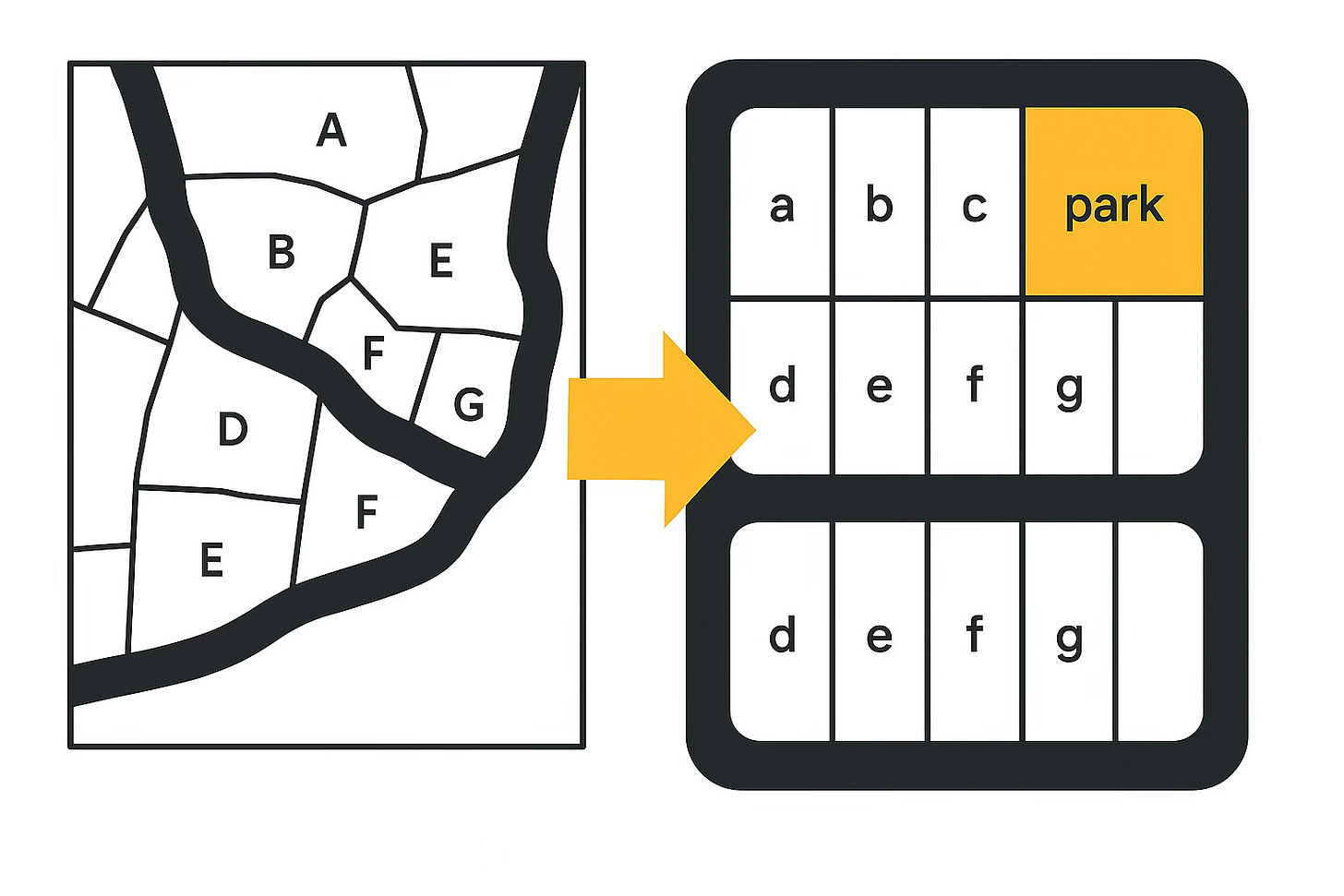

Let’s take the diagram above as an example. The map on the left shows the starting situation: a series of irregular land plots with different owners and some roads. This layout wouldn’t be particularly efficient or suitable for a more urban context. And there is no land for public use. This means that even if you developed individual parts of this land, you wouldn’t be able to realise the full potential of the area that would come by replotting it from scratch.

This is where land readjustment comes in. Land readjustment empowers an entity to change the land plots, with the consent of landowners. The new plan uses the land more efficiently, with a better road network and even retains some land for public use too. This increases the value of the land plots significantly, even though they’re a little smaller than before.

Landowners are incentivised to do this because they will own land in this new development and therefore share in the value it creates. Without land readjustment, you couldn’t have given landowners a stake in the upside of the redevelopment as they would have needed to sell the land to you. This would have been very expensive.

There is a policy tool for some situations like this: compulsory purchase order (CPO). A CPO could have been used to take the land from landowners in exchange for compensation, but CPOs are politically unpopular and slow.

As my colleague Sean O’Neill McPartlin recently wrote, where before policy provided just a stick, with land readjustment, it can provide a carrot too. The result is plots of land that are suitably arranged for development and serviced with the infrastructure and utilities needed to fully realise their value.

Ireland currently has no land readjustment provisions in law. If we did, what kind of impact might they have?

The impact in Japan

Land readjustment has been a key part of the Japanese urban development story for more than a century. In the six decades from 1954 to 2013, the country completed almost 10,000 land readjustment projects – an average rate of three a week.

The impact has been staggering. Thirty percent of Japan’s built-up environment has been created or redeveloped by land readjustment. It generated a quarter of the length of all city roads in Japan’s cities (11,500 kilometres) and half the country’s total area of community parks, neighborhood parks and district parks (150 square kilometres). A third of station plazas at stations with over 3,000 passengers per day have been built thanks to land readjustment (950 facilities in total).

Aerial photographs of the Shiodome project in Tokyo help show the scale of the achievement in just one area of one city:

Case study: Akihabara Station Area project

To see how this works in detail, let’s take a look at a particular case study: the Akihabara Station area project in Tokyo.

In the early 1990s, a large amount of land near the station was vacant, once used for a public vegetable market and a freight depot. Land readjustment was needed in order to replot the land so it was suitable for a new purpose in line with long term development plans: a mixture of commercial, residential, and cultural facilities.

Though there is variation across projects, the broad features of land readjustment in Japan are as follows.

First, the process is initiated by either a landowner association, local government, or national government. The boundaries of the project area are legally defined before anything else happens, as otherwise it wouldn’t be clear what area and whose land you were actually talking about.

Next, a legal entity is created to carry out the project. Its board of directors can be used to give landowners a voice, perhaps via delegate board members, as well as any other entities involved, such as local or national government.

A new plan for the area is drawn up by the entity, including a survey of the land and a financial calculation to ensure the plan is viable. This should include any government subsidies and tax breaks, and the amount of land that will be given for public use.

Importantly, landowner consent is then sought. Landowner association-led projects have an explicitly democratic element, requiring that a supermajority of sixty-six percent of landowners owning sixty-six percent of the land must sign a contract for the project to continue. An additional round of consent sees specific plans endorsed by the landowners, such as the land contribution of owners to the public and the financial details.

After that, construction can begin. New roads, parks, and utilities are built as laid out in the plan. This is where the value is really generated for all involved in the project, and once it’s complete, the area is ready to transform into a denser and more economically productive area. When the project is completed, the organisation dissolves.

In the Akihabara project, landowners contributed an average of thirty-five percent of their land for public use. You can see before and after pictures of the area below, or hop onto Google street view around the area to get a sense of the transformation.

The results speak for themselves. Four new roads, two new plazas, and a park. Over a hundred new apartment buildings with a total floor area of 480,000 square metres. A twenty-seven percent increase in population. A ten-fold economic multiplier, due to the project’s construction phase and private construction development as various buildings were relocated.

The lessons for Ireland

Progress Ireland is developing a policy proposal for land readjustment in Ireland. Ireland is coming to land readjustment late, but that means we can learn from Japan’s decades of experience making it work. There are three key lessons to bear in mind.

First, the democratic consent of landowners helps legitimise land readjustment. Much like another Progress Ireland policy, street plan development zones, holding a vote among landowners allows everyone’s voice to be heard and means that any development has durable support from those it will affect most. Japan’s sixty-six percent threshold for support also means that land readjustment can’t squeak through with a 51-49 majority; only projects which most landowners want will happen.

Second, sharing the value generated by land readjustment gives everyone an incentive to participate in development. By contrast, CPOs give landowners no share in the potential upside of development. Landowners are paid off with an amount that might not even cover what they paid for the land in the first place, so they often fight against CPOs.

Land readjustment incentivises cooperation among landowners and makes it less likely that someone will want to hold out against development in their area.

Finally, there is huge upside available if Ireland can get this right. Japan’s extensive use of land readjustment shows that it can help transform urban areas at scale. This is sorely needed in Ireland as we deal with a growing population, dereliction and changing land use patterns, and homeowners concerned about rapid development. If we can get our cities growing sustainably, we’ll see the benefits in public health, climate, and the economy. Land readjustment can help make that happen.