Next week, the National Planning Framework (NPF) will be approved by cabinet. The NPF is Ireland’s most important planning document. It sets targets, controls how much land gets zoned, and sets the tone of national policy.

It is important that the NPF gets approved quickly, so that the higher targets in the new NPF can take effect and local authorities can follow suit.

The last NPF’s housing targets were too low. They were based on data from the 2016 census. The new NPF will be updated using the 2022 census and recent work by the ESRI. The targets will move from 33,000 a year to 50,500 a year (and are supposed to be scaled up to 60,000 a year by 2030).

The move to raise national targets is welcome. But the NPF has important problems that ought to be fixed in the newest version.

Last week, I wrote about the problems with the old NPF (which you can read here). The short version is that the NPF makes housing scarcer and more expensive in the east of the country. It does this by capping housing growth in and around Dublin, Ireland’s greatest employment hub and most important city.

This week, I want to talk about some constructive proposals of how to remove the cap. These changes don’t have to be controversial. Most of the changes have backing from the Housing Commission, the most recent OECD Economic Survey report for Ireland, the recent Irish Cities in Crisis book, and reports from Savills and Goodbody.

The NPF caps development in Dublin with the goal of achieving regional balance. And its plan is ambitious. 50 per cent of growth is earmarked for the Eastern and Midlands region (which contains Dublin) and the other 50 per cent for the Southern, Northern, and Western regions. 25 per cent of national growth is earmarked for Dublin and its suburbs, another 25 per cent to the other cities, and the rest to towns and villages.

The problem with this policy is not the targets, but the tactic by which the NPF seeks to achieve them. There are two ways the NPF seeks to achieve these targets. One is helpful, the other is damaging.

The NPF’s first tactic to achieve regional balance is to make Ireland’s regions more attractive as places to live, work, and invest. The NPF seeks to direct national investment in the infrastructure required to make all of Ireland’s regions competitive. This is basically a good idea. The NPF has gotten this part of the approach right.

The NPF’s second tactic to achieve regional balance is to suppress growth in the east of Ireland. The idea here is that growth will flow, like water through a canal, from the east to the west, north and south of the country. I explained exactly how this works last week (here) but the short version is that growth does not flow like water; if you block a home in Sandyford, it doesn’t appear in Skibbereen. The cap means less land is zoned for housing in Dublin, fewer homes are built, and rents and house prices continue to grow. Dubliners who want to live in Dublin have to leave (driving up prices in the commuter counties) and people from around Ireland who want to move to Dublin for work or study can’t. Dublin loses and no one else wins.

First suggestion: Pick the higher targets

The first way to fix this is not to change the 50:50 rule in the NPF. As I said, the goal is fine and it’s politically popular. What can change is the means by which the NPF achieves it.

The cap is operationalised through inputs called the Housing Needs and Demand Assessment (HNDA) and the Housing Supply Targets (HSTs). The HNDA is a tool used by local authorities to assess the housing needs of their area. The output of this process is the local authority’s HST.

The NPF’s regionally balanced population goals feed into the HNDAs, and in turn the HSTs. The upshot is that in Dublin and the east, the amount of zoned land is lower than it would otherwise be.

Removing the cap is something the Minister can do at a stroke of a pen. Here’s how it would work. When preparing a HST, local authorities consider a range of ‘scenarios’ provided for in their HNDA. These were helpfully presented in the following table by Carla Maria Kayanan here as follows:

At present (prior to the new NPF’s goals), ‘convergence’ is the default scenario for councils when preparing their HSTs. Divergence from this default must be rigorously justified and defended.

As before, where the NPF figures are lower than the other scenarios, the resulting target is lower than it otherwise would be. This works by splitting the difference. If the NPF wants 10 people but the ESRI’s projection is that the area will need 20, the resulting HST is 15.

This could be changed to remove the option for the NPF’s targets to decrease the ultimate HST. What this would mean is that where the ‘high migration scenario’ (which, incidentally, is lower than each of the last three years of net migration) is higher than the NPF’s target, the council would have to choose the higher number. No splitting the difference.

To illustrate this minor modification to the HST process consider a simple example. A council in Dublin is preparing their HST. They take a look at their HNDA spreadsheet. The NPF’s default scenario aspires for 10 additional people in the area. But when they look at the high-migration scenario, it looks like there may be an additional 30 people in the area. This proposal says the council should always pick the higher number.

The NPF says it does not seek to limit the potential of Dublin. But the way the NPF’s targets work on the ground demonstrably does just that. This small change would show that while the NPF seeks to enable more regional balance, it will not place caps on Dublin.

Crucially, this change would still allow the NPF to increase the quantum of zoned land in those places where the NPF’s goals exceed predicted demand. This change allows the NPF to boost Ireland’s regions without suppressing Dublin, a win-win.

To fully remove the cap, the Minister would need to reissue the HNDA and HST methodology to reflect the removal of the ‘cap’. Each document would need to make it explicit that councils must prepare their targets using the highest growth scenario.

Alone, this fix won’t totally align the targets with actual need. The high migration scenario may be insufficient and arguably the assumptions around household size could be improved. However, this small change could be achieved next week. And the small change could make a big difference, not just to the capital but to the entire country.

Second suggestion: no more dezoning

Dezoning is when land which was available to build on is removed from a plan. Land can be rezoned or dezoned for lots of reasons. But in the last few years, there have been cases of land being dezoned because (among other things) housing supply targets have been met. It is hard to get a sense of how many cases have been hinged on exceeding targets because usually many more issues are cited (most typically, infrastructure deficits).

To prevent both the perception and reality of dezoning, the new NPF can add a simple sentence instructing all tiers of the planning system–including the courts–that no land should be removed from availability or ‘dezoned’ due to the area exceeding its targets.

The government has already made an important step to remove this problem when it comes to planning permissions. Prior to the Planning and Development Act 2024, planning permissions could be denied on the grounds that the area has met its housing supply targets. Section 86(7) of the 2024 Act fixes that.

But the problem remains for land. This small change would fix that and could replicate the language in the 2024 Act above.

Third suggestion: fix conversion rates

To set a housing supply target, councils must assess their needs. But they also need to take into account the conversion rate between zoned land and delivered homes. Getting the conversion rate right matters. If you undershoot it, you will bake-in undersupply.

The last Dublin city development plan assumed a conversion rate of 54 per cent: about half of all land zoned will be converted into homes. Its land survey said that 550 hectares of available land could “provide approximately 48,500 residential units.” Given that the housing supply target for the council at that time was 27,000, that means that 55 per cent of the land would have to be developed to meet the target.

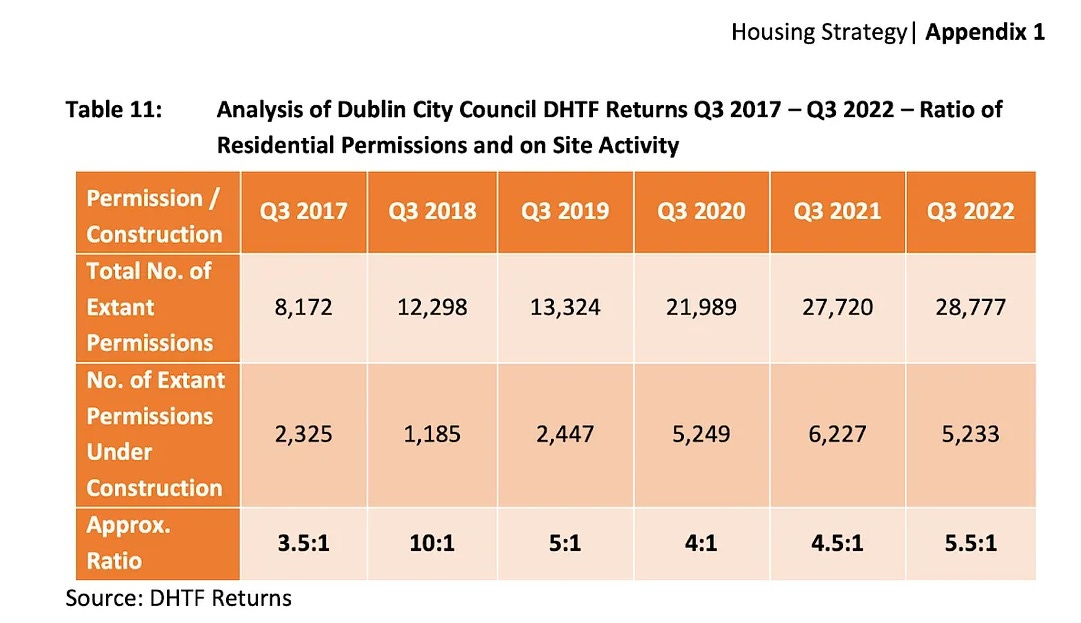

That figure is far too optimistic. The historic conversion rate between residential planning permissions and commencements in Dublin is about 4:1. So, even if a permission were granted on all of the 550 hectares, we should only expect about a quarter of them to turn into new homes in a cycle.

Housing Supply Targets should reflect the historic conversion rate of the council’s area. While councils do take conversion rates into account, the HST guidance does not require that they do. Local authorities should be required to zone a sufficient amount of land based on historic conversion rates. As before, in Dublin this would mean assuming that only a quarter of permissions will convert into homes in a given cycle.

To fix this, the Minister for Housing, Local Government, and Heritage could add a simple line in the HST methodology document requiring that historic conversion rates be built into the final target.

Fourth suggestion: Increase the buffer

Councils have long been required to apply some ‘headroom’ in their development plans. The idea is that they ‘oversupply’ land due to, as before, conversion rates. Headroom rates are currently at 25 per cent.

Sources such as Goodbody are now recommending that councils allow for 40 per cent. But it is worth remembering that until quite recently headroom or ‘buffer’ allowances were as high as 50 per cent.

Restoring this historic ‘buffer’ of 50 per cent would be a positive step to tackling the undersupply of land, especially in the Eastern and Midlands Region. A higher rate of 100 per cent could be applied to the city councils to promote compact growth and combat sprawl.

Fifth suggestion: Do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good

The NPF requires a minimum of 40 per cent of development to be ‘compact,’ meaning it is within existing settlements. Land that is available to build homes can be removed from a plan if it is judged to be not sufficiently compact and so contravenes this 40 per cent target.

The trouble is that delivering compact growth is slower and more expensive.

According to one study, commencements on greenfield sites in the Eastern and Midlands region took an average of 13 months whereas brownfield sites took about 20 months.

Planning refusal rates are also higher for brownfield sites at 22 per cent versus 18 per cent for greenfield sites. These delays make them more expensive, as shown by this graph from the Department of Finance. The longer the planning delay, the lower the returns.

The other problem is that it is a zero-sum policy. We shouldn’t decide that a housing estate shouldn’t be built because we want something to be built on an existing site closer to a town or city centre.

This will have costs, of course. But so will continuing the de facto cap on greenfield development. Pushing people who work in Dublin into commuter counties may technically count as ‘compact growth’ but that is not environmentally sustainable.

Encouraging compact growth in Dublin’s commuter belt while capping Dublin has led to long commutes. It isn’t obvious that this is the greener solution compared with building more in Dublin and improving transport in the capital. Tokyo has a big footprint but is functionally quite compact given its impressive transport network.

We need to move away from the attitude that the only housing that should be built is the kind that ticks every national policy box. I have heard a lot of that attitude in the seomraí debate. Critics say we shouldn’t build seomraí, we should build [insert your favourite typology.] Whereas, I believe we should be saying yes to every kind of new residential development.

One underrated reason to support removing the cap on greenfield development in the NPF is political. Brownfield developments meet much more local oppositions, unsurprisingly, because the development is near other people and sometimes imposes a cost on them. Greenfield development is cheaper and faster partly because delays caused by objections are rarer.

Preventing economically and politically viable housing delivery while the country is missing its delivery targets strikes me as a mistake. The NPF can be amended to ensure that, while it retains the 40 per cent compact growth target, that target is not interpreted as a cap on greenfield development. The wording here, as before, can reflect section 86(7) of the 2024 Act.

Sixth suggestion: Test for viability

The previous five suggestions would, if implemented, significantly increase the amount of zoned land, especially in the Eastern and Midlands Region. While I believe that worries around oversupply are overblown, it is reasonable to want some guardrails on the increase in land capacity.

One way to put a natural limit on the above suggestions is to require a ‘viability’ test for zoned land. The basic idea is that if it is commercially viable to build on the land – meaning that a development could be delivered at a profit – then that land is not ‘oversupplied.’ The viability of the development is a signal of sufficient demand, in other words, if it is commercially feasible to build, then people want to live there.

This would ensure that land supply does not become severed from demand. And the idea has significant support from the Housing Commission and the industry.

The current New Zealand government is implementing a viability requirement on council’s plans to ensure that the land zoned will be converted into new homes. They call it ‘feasible development capacity.’ And councils there will soon be required to provide 30 years of feasible development capacity in one swoop.

There are many ways to implement a viability test and I won’t adjudicate them here. But the basic idea is that, if there isn’t demand to build somewhere, councils shouldn’t be able to say they have zoned enough land to meet their targets. If it isn’t viable to build, there will be no private development. A viability test will ensure zoned land actually contributes to meeting targets.

A note on infrastructure

Of course, while these proposals will increase the amount of zoned land, they will not–on their own–increase the servicing of that land. The NPF (and related documents) can be changed to enable greater levels of land availability. Other rules will need to change to get that land hooked up to the pipes, drains, and wires required to deliver new homes.