Radical planning reforms in the UK: too much of a good thing?

First the policy, then the backlash.

There is a word for knowing what must be done and failing to do it anyway. Socrates called it akrasia (an Ancient Greek word, ἀκρασία, sometimes translated as “weakness of the will”).

Why do we fail to do what we ought to do? This question is at the heart of housing shortages across the developed world.

We know what to do: build more homes. We know we will get more homes built by making it easier to build. We know the simplest way to make it easier to build is to loosen planning. But if we know what to do, why don’t we do it? Why is it so hard?

The first answer is that we suffer from akrasia — in other words, that housing policy has simply been too cautious. “To get more homes built, governments must be more aggressive in their reform”, is the argument. The Eoghan Murphy approach.

But students of philosophy will remember Socrates thought genuine akrasia was impossible. He thought it was impossible to know you should do something and fail to do it. His explanation for not doing it is not that you’re weak, but that you don’t truly believe that it is best. Socrates would say we haven’t solved the housing shortage because, on some level, we don’t want to.

Why don’t we want to build? The hardest part about building lots of homes is managing the backlash from neighbours. As much as people say they want to solve the housing shortage – and they do, in fact, say this – the most radical measures would meet massive political resistance.

All of this suggests two strategies. If the problem is merely a weakness of will, the solution is to get building and face down the backlash. I’ll call this the idealist strategy.

If the problem is that our conflicted feelings about housing make it impossible to get things built, the solution is to minimise our conflicting feelings about building. I’ll call this realism.

Cards on the table: I’m in the second camp. I think the hard thing about housing policy is the politics of it. The task of housing policy, on this view, is to figure out how to build the coalition for building. This is Progress Ireland’s M.O.

Radicalism in the UK

The British Government has no time for this coalition-building stuff. An extraordinary set of recent reforms in the UK is taking a sledgehammer to their restrictive planning system. The British government’s diagnosis is that policymakers have been too sheepish. Their solution is to unleash huge amounts of building and face down the backlash.

The gambit could well pay off. But I would be surprised if some of it will last past the current government. What are the reforms?

The reforms were announced last week in the National Planning Policy Framework or NPPF consultation document by Matthew Pennycock. The reforms will create a presumption in favour of development, automatically unlocking huge numbers of sites around train stations, and allow for large amounts of suburban development.

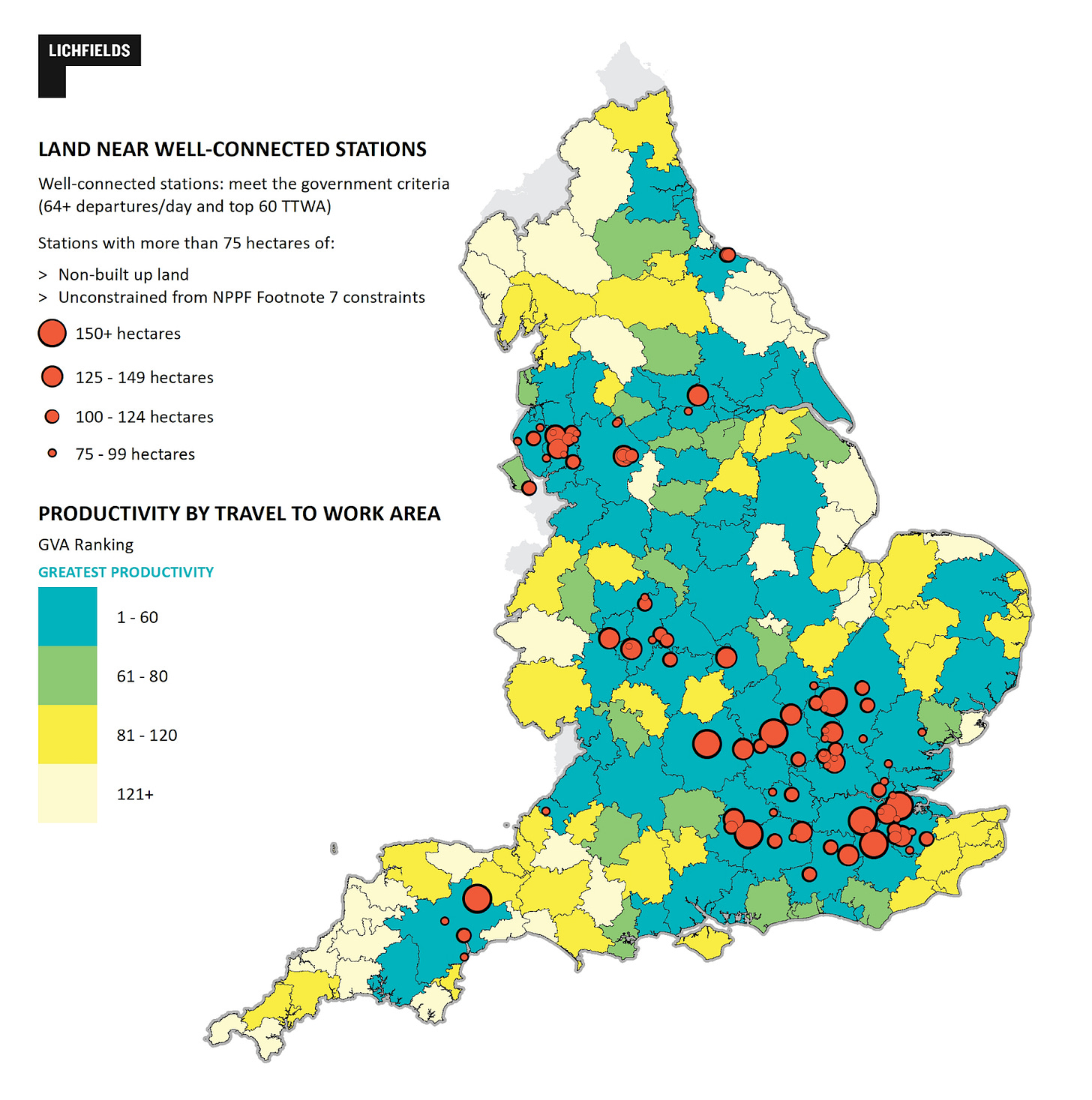

The short reason why I suspect there will be a substantial backlash is that the reforms will work, in that they are likely to deliver a lot of homes. One of the announced reforms will permit high densities near train stations. Minimum densities of 40 dwellings per hectare will be permitted near well-connected train stations linked to the 60 most productive travel to work areas defined by gross value added. Near the best connected stations there will be a minimum of 50 dwellings per hectare.

On its own this change could deliver somewhere between 600,000 and 2.1 million new homes, depending on assumptions about site ratios and density. For context, the UK built around 100,000 homes in 2024.

But despite the promise of delivery, as it is currently drafted, there is little in the reforms that will directly benefit the locals who may resist the disruption and change caused by massive amounts of building. If some of the value created by the huge amount of building is not redirected into the likes of increasing train capacity, improving roads, delivering on public realm improvements, then I suspect the backlash will be strong.

The idealists have a response, however. In New Zealand, the Auckland Unity Plan (AUP) created a default ‘yes’ near train stations. The plan led to a housing boom and rent to income ratios fell. This policy has been a massive success and the new Auckland plan looks to be building on the success of the AUP. The idealist interpretation of this story is that it proves the idealists point: if you bravely build huge swathes of homes, you can weather the storm of the backlash.

But the idealists would only be partly right in extracting this lesson. It is true that Auckland built a lot of homes, an additional 21,000 homes were built after the 2016 Auckland plan. At least half of the new supply was directly due to the reforms. But attempts to bluntly generalise the lesson – a policy called the Medium Density Residential Standards or MDRS – of the AUP failed.

The current Kiwi government has learned the realist lesson. Their housing plan (called “Going for Housing Growth”) is split into three pillars. The third pillar explicitly takes the realist line. It aims to “provide incentives for communities and councils to support [housing] growth.” They have provided opt-outs, giving locals choices over how best to meet housing demand. Councils can choose the MDRS or they can meet housing demand another way. In fact, the most recent Auckland plan opts out of MDRS, though it is no less ambitious for it.

A pillar of the British reforms is a presumption in favour of development within towns or cities. This means that, so long as some rules are followed, development will be permitted in most towns and cities by default. When this gets through, councils’ ability to stop development will be greatly reduced.

In California, the history of YIMBY campaigning is in part a history of a cat and mouse game between local and State government. The state has been trying to force development on local authorities. And locals have found ways innovative around the state decrees.

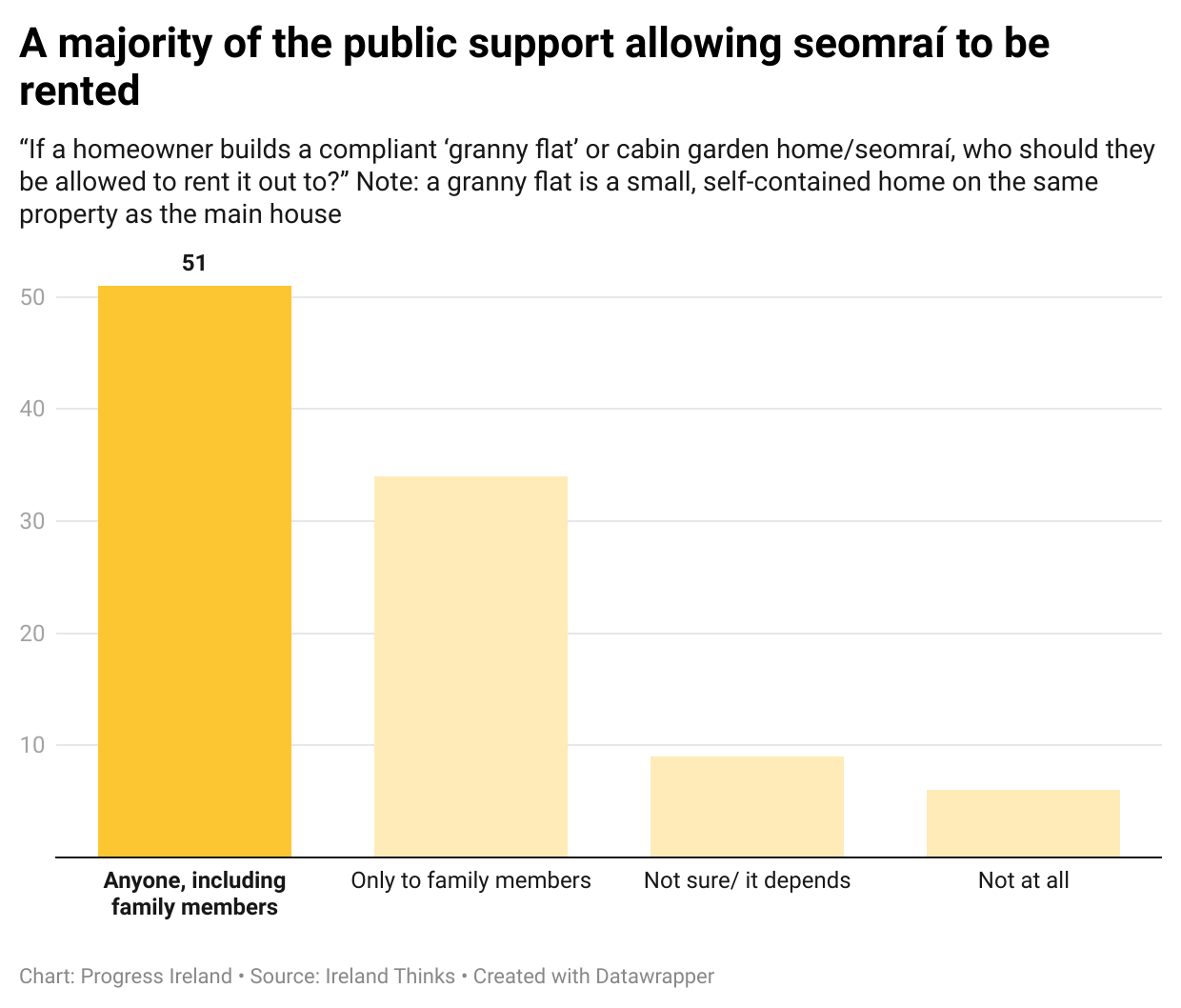

More controversial still is the NPPF’s plan to intensify suburban development. In Ireland, allowing a 40sqm seomraí in suitable gardens was a national debate. In the end, the majority of the public supported the idea. Here again, this seems like a victory for the idealists. If you win the argument at the national level, you can force local governments to accept more suburban development.

But the NPPF goes a lot further than Ireland’s seomraí. It will allow multiple apartments to be built in some gardens. The suburban policy will also allow seomraí, upward extensions, mansard roofs, and additional densities in corner plots.

The controversy will come, I predict, from the plan to allow multiple new units in gardens. This idea follows from a short-lived but successful policy in Croydon which allowed apartments to be built on existing sites. The policy delivered about three times as many small developments as neighbouring boroughs. But it was hotly contested and ultimately repealed.

The ambition and courage displayed in the UK’s NPPF must be applauded. We’re about to witness a rare experiment on the merit of railroading local stakeholders as a means of solving a housing shortage.

Great article, though I think the MDRS coverage isn't quite accurate. The sequence of events was:

- Labour passed the MDRS with bipartisan support from National

- National later changed position going into the election (likely due to a change in leader who is less YIMBY) and campaigned on letting councils opt-out of MDRS if they zoned for 30 years of growth

- National won the election and then earlier this year the housing minister, Chris Bishop, announced he was removing the ability for councils to opt-out except for Auckland and Christchurch (announcement here https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/saying-yes-more-housing)

Chris Bishop said removing the ability to opt-out was a pragmatic decision because councils had already incorporated MDRS into their plans and it would take years to change this to "zoning for 30 years of growth". I suspect another reason was that it became apparent how difficult it was to determine and police whether a council had actually zoned for 30 years of growth - it's extremely sensitive to population growth estimates for the region and councils could claim compliance even if much of the zoned land was in areas that were uneconomic to develop due to lack of infrastructure.

Well argued, and you could indeed be right. I think NPPF does not require primary legislation so an incoming government could quickly water down the policies and Reform, Lib Dem’s and Green’s are all to a degree NIMBYish, and I observe in hope that the Tories may recant their ways. Given the current government could stay in place till 2029 there will be a lot of planning permissions issued. Grey Belt looks like it’s already moving the needle.