Speculators are a Red Herring

The reason housing is scarce and expensive is not speculators

Read enough about housing and you will hear about the speculator.

Conversations about housing usually pass the usual stops. Prices are too high. There are not enough of them. If you ask “why?” enough times, lots of serious people will place the blame on the speculator.

There are two problems you will encounter at this point in the conversation.

First is that it is rarely clear what “speculation” means, if anything. Sometimes it refers to land hoarding. Other times to excessive trading. Some people use it to mean the practice of making a financial return, per se. Still other times it is an empty scapegoating term, meant to capture a cluster of things your conversational partner doesn’t like about housing.

Second, when you pin down a precise meaning to the term, it turns out to be hard to believe that “speculation” is one of, if not the most important, driver of Ireland’s housing problems.

It is easy to find the blame for Ireland’s housing shortage being placed on the speculator. You can find it from the EU. Walk down the TUD, and you will find it from housing professors. You can find it from architects, like here, here, and here. The Irish government briefly toyed with the idea of blaming speculators. You can even find it from Jesuits (perhaps unsurprising because Pope Francis criticized speculation). It’s a common, powerful, and enduring strain of thought. But who are the speculators?

As you might expect, it depends who you ask. At a high level, speculation usually means the holding or trading of an asset in the hopes of making a return. When you invest in your pension, you’re speculating in that sense. Most homeowners are, to some extent, speculators in this sense too. But used in this way, as it is by some, its target is the use of the market in general, and doesn’t refer to any particular activity within the market. But that is too broad a use to capture what most people mean by the phrase.

For others, land speculation refers to fairly specific activities. One kind of activity it refers to is “hoarding” land. This means holding onto valuable sites and deliberately leaving them vacant. The idea is that the speculator is awaiting more favourable terms (a change in interest rates, a spike in demand, a change in government policy). Once those favourable terms are met, they will get building. Henry George, whose book sales were only beaten by the Bible during the 1890s, said speculation is about withholding “valuable land,...from use.”

Paradoxically, speculation can also refer to the opposite behaviour: excessive trading. When people blame speculators, they sometimes have in mind something like a game of pass the parcel. They imagine a group of rentseekers, indefinitely trading assets. With each transaction, land prices are driven up more and more. Ultimately resulting in higher rents and prices for the end users.

The slipperiness of the term makes it hard to evaluate. But there are parts of the idea that can be discussed simply.

The first part of it relates to vacancy. George seemed to think the principal symptoms of speculation are high levels of vacancy (land being “withheld”) and high land prices. This is the speculative “hoarding” that is sometimes discussed. So, high levels of hoarding should be visible in the data in the form of high levels of vacancy.

The second part relates to land prices. If high and rising land prices are the main driving force of increased costs and prices, then their proportion in overall development costs should go up over time. In short, more and more of the price households pay should be due to land. This could be the result of hoarding or of frenzied transactions. But the telltale sign should be that land costs make up more and more of development costs.

Similarly, if land is being hoarded in the hopes of speculative windfall, then we should expect agricultural land prices to be very high.

The third part relates to planning permissions. If speculative “holding” is a driving force of cost pressures, we should see high numbers of unactivated permissions as landowners “wait” for more favourable conditions.

It makes sense to focus on land. After all, land is unlike other assets. Land holding acts like a monopoly: If I hold a piece of land, no one else can have it. The economists say that the supply of land is fixed or as real estate people say: they ain’t making any more of it. It isn’t fungible, like some other assets. It can (usually) not be created. The value of well located sites goes up over time. But let’s try to get more specific about the kinds of speculation I have in mind.

Different kinds of speculation

One thing that gets called “speculation” is when a firm buys a plot of undeveloped land, seeks and receives a planning permission, and then sells the land for a premium. With planning risk removed, the price of land goes up.

But this isn’t in itself a sign of dysfunction. As always, when prices go up, we shouldn’t shoot the messenger. The increased price tells you as much about planning risk as it does anything else. The premium for land with a permission is about 10 to 20 per cent (though there is little data to back this precise figure up). This premium reflects the difficulty involved in getting planning permission for sites. If it were easier to get planning – or in other words, if the planning system were more specific – that premium would dwindle. The increase in value might be exacerbated by trading, but the practice does provide some value. One report notes, however, that this sometimes useful practice is not that common in Ireland.

But there are less productive kinds of speculation too.

One example is related to zoning. Agricultural land gets traded in the hopes of a rezoning decision. Rezoning increases the value of a plot by about 8,400 per cent. People trade land in the hopes of striking gold, when the colour of the rezoning map changes.

Still another kind is related to hoarding. Land is “hoarded” in order to wait for more favourable conditions, which may or may not overlap with the other kinds of speculation. For example, government housing and planning policy has changed in the last few governments. Even though few are happy with the state of housing policy, some argue that policy shouldn’t change because change invites speculation.

For others, speculation is baked into the use of the private sector and the practice of seeking returns itself.

To make things concrete, I’ll try to focus on specific forms of speculation.

George seemed to think the principal symptoms of speculation are high levels of vacancy (land being “withheld”) and high land prices. If land prices were high, you would expect more and more of overall development costs being due to land. You would also expect large numbers of transactions, as the speculators pass the parcel around.

From my reading of the evidence, I can’t see any of these signs of rampant speculation. I’ll go through each in turn.

Valuable land, withheld from use

Let’s look at vacancy first.

The first thing to say about vacancy is that there is little data on the kind of vacancy that relates to “land hoarding” or speculation. What we do have is data from the government’s RZLT dataset but that doesn’t show a lot, for example, it doesn’t show ownership.

Nevertheless, we do have a lot of data on the vacancy rates of dwellings. Data about vacancy rates (or “long term” vacancy, ie four consecutive quarters) comes from the CSO. If a dwelling is using less than 180 kilowatt-hours per quarter, then it is considered vacant.

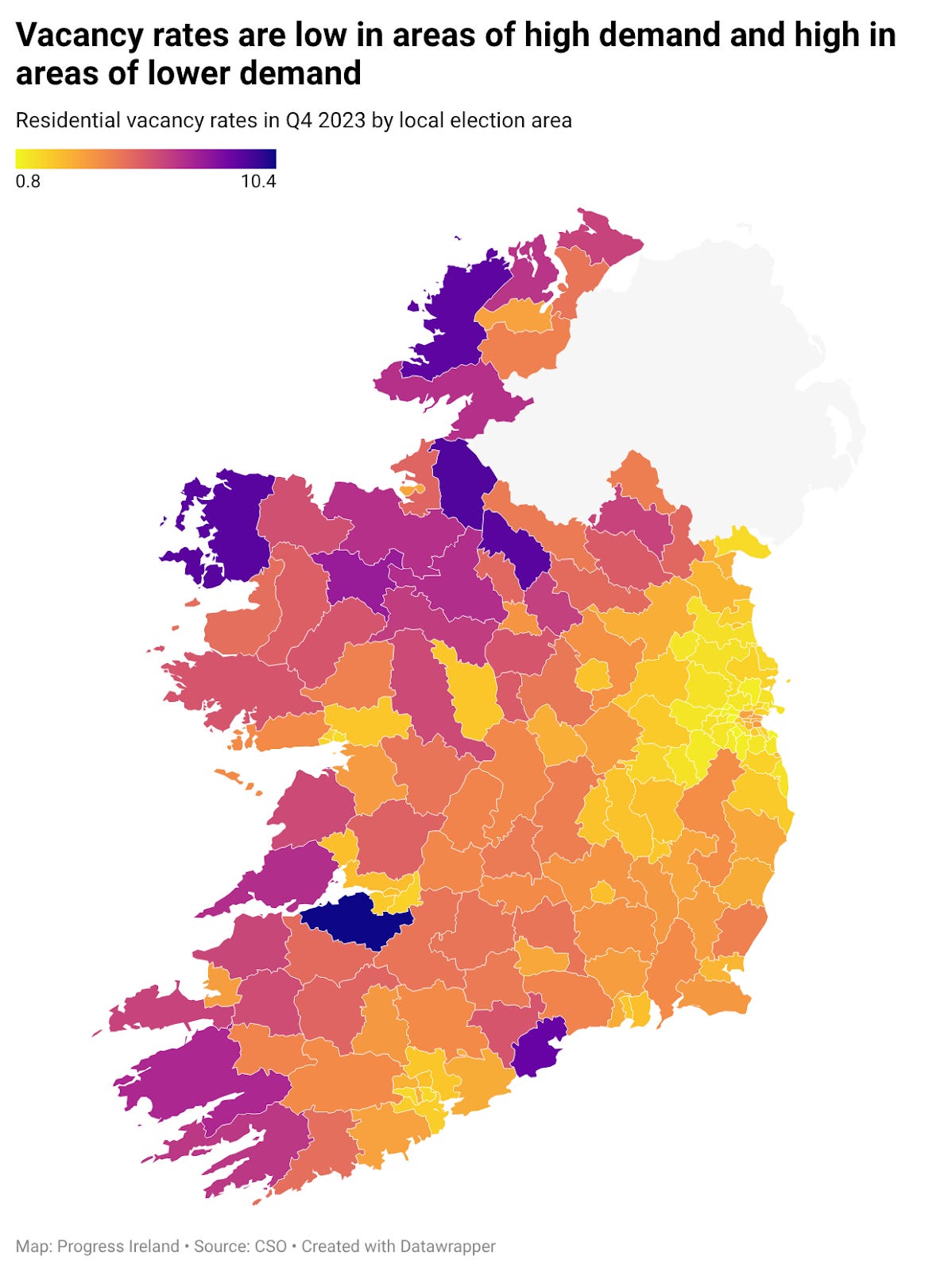

If the modern Georgist idea is right, that hoarding valuable sites is a widespread and consequential problem, then we would expect to see high levels of vacancy. More than that, we would expect to see high levels of vacancy in the highest demand areas. Withholding an unpromising piece of land would make for dubious speculation.

The second thing to say about vacancy is some level of vacancy is not just expected, but is desirable.

Policymakers sometimes refer to a “healthy” vacancy rate of about 5 per cent. The reason why a functional system should have some vacancy is that people move around. If all homes are filled, then mobility falls. That means, people can’t move to better jobs, to be nearer family, or to downsize. A functional system will have some mobility as people move jobs or relocate for other reasons.

The third thing to expect is that areas with high demand will have lower levels of vacancy than areas with lower demand. A healthy system will match people to empty homes faster in areas with higher demand. You should expect prosperous cities to have lower vacancy rates than sleepy villages.

As George said, unusually high levels of vacancy is a symptom of “hoarding” or speculation. So, how is Ireland faring?

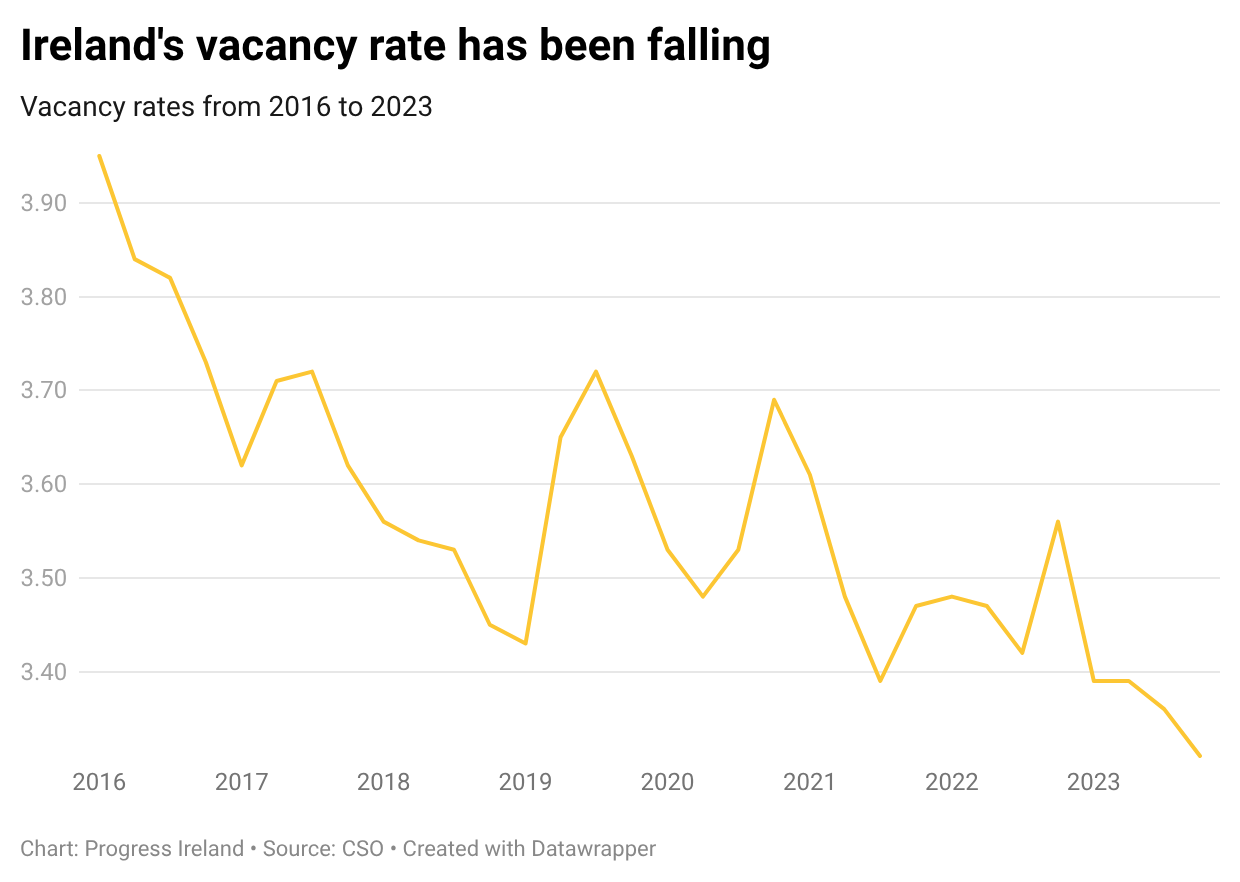

Across Ireland, vacancy levels have been falling.

Dublin in particular has unusually low levels of vacancy. In South Dublin, the vacancy rate hovers around just 1 per cent. In Dún Laoghaire, vacancy levels are at just 0.9 per cent. As you would expect, vacancy levels outside of Dublin and Cork city are typically higher.

This makes me think that if “hoarding” is putting upward pressure on vacancy rates, the effects are very small. The pattern of vacancy across the country looks roughly as you would expect, absent hoarding. In the highest demand areas, there are very low levels of vacancy. This is to be expected in a tightly undersupplied market.

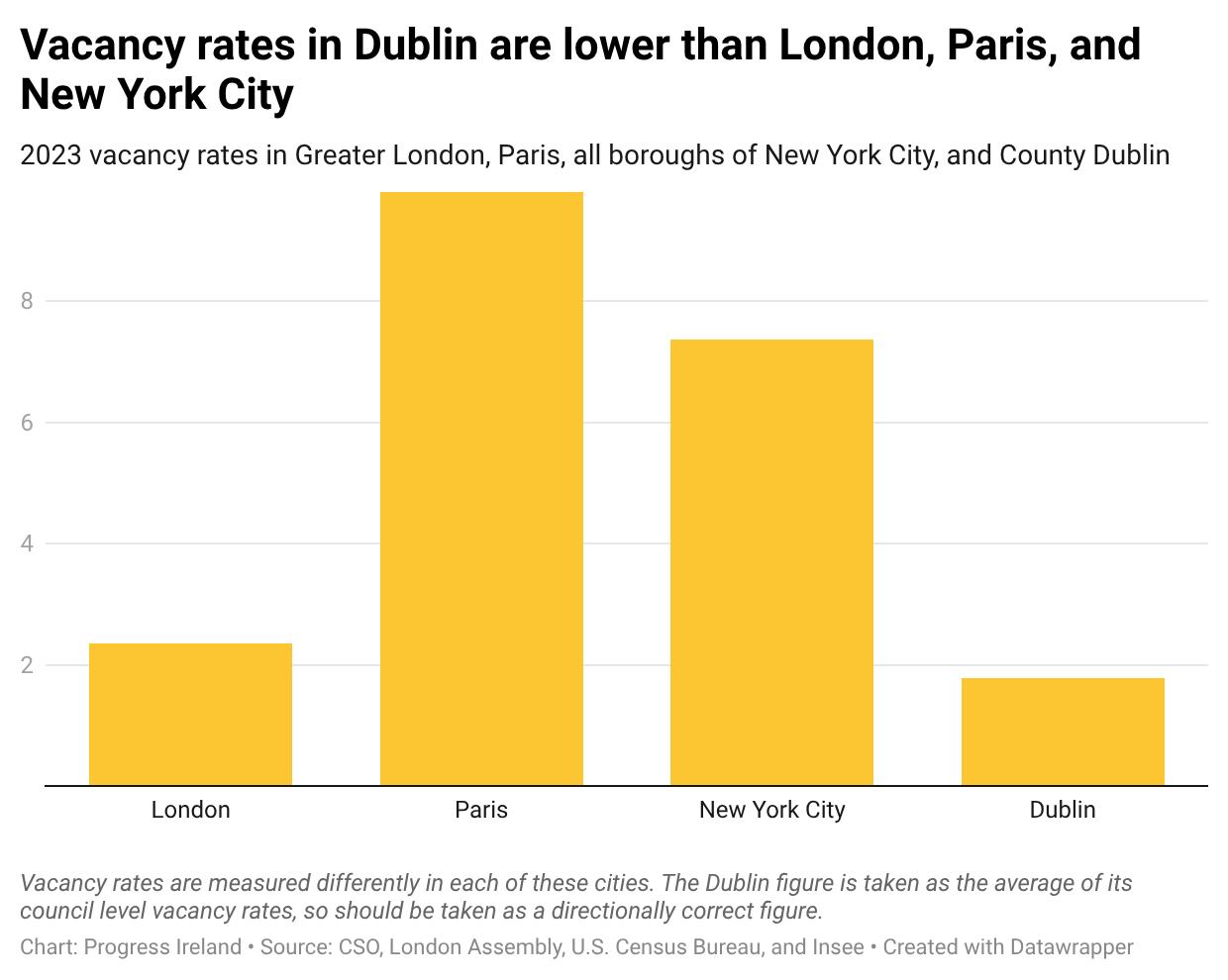

The levels of vacancy in Dublin are unusually low by international standards. New York, Paris, and London all have higher vacancy rates than Dublin.

Land prices

Next is land prices. If speculation was the biggest, or one of the biggest, drivers of rents and house prices, we should expect land prices to be on the rise.

The first thing to say about land prices is that they are somewhat opaque. This is due, not least, to the fact that Ireland has no single source of wisdom on the availability of zoned and serviced land. There has been a steady flow of recommendations suggesting that Ireland needs a centralised dataset on land availability and its status. Notwithstanding the difficulties entailed by a land value register, this would help government figure out which local authorities are complying with Section 28 Housing Growth Requirements (a task which has been left to the Office of the Planning Regulator).

The second thing to say about land prices is that it is difficult to decompose the contribution made by land prices into prices and rents precisely.

In the scenario in which hoarding and speculation is driving up prices and rents, you would expect that land would contribute more and more to the cost of delivering a home (and indeed, the price that that home sells for). As a proportion you would see labour, materials, planning, design and so on would fall as contributors to costs and prices. Is this what we see?

There is some anecdotal evidence that, during the Celtic Tiger, land prices made up about half of the price of a new house. It is widely believed that speculation (of the unproductive sort discussed above) played a major role during the period.

But since then, the contribution of land to costs have fallen. If inflated land prices made up half of prices back then, they only make up about 13 per cent for houses and between 9 and 11 per cent for apartments.

When looked at in a different way, the answer is roughly the same: land costs make up in the region of 10-15 per cent of prices. A paper by Kieran McQuinn used a different methodology than the SCSI report above. Put simply, it looked at the difference between house prices and construction costs to find the “residual” or the left over bits. Of that residual, McQuinn found that by 2023, land costs made up roughly 25 per cent.

Compared with other contributors to housing costs (construction costs make up about half), land seems to hold a significant but not huge place. Compared with the figures cited during the boom, there is little evidence to think that speculative or hoarding behaviour of land is a unique driver of the cost of delivering homes.

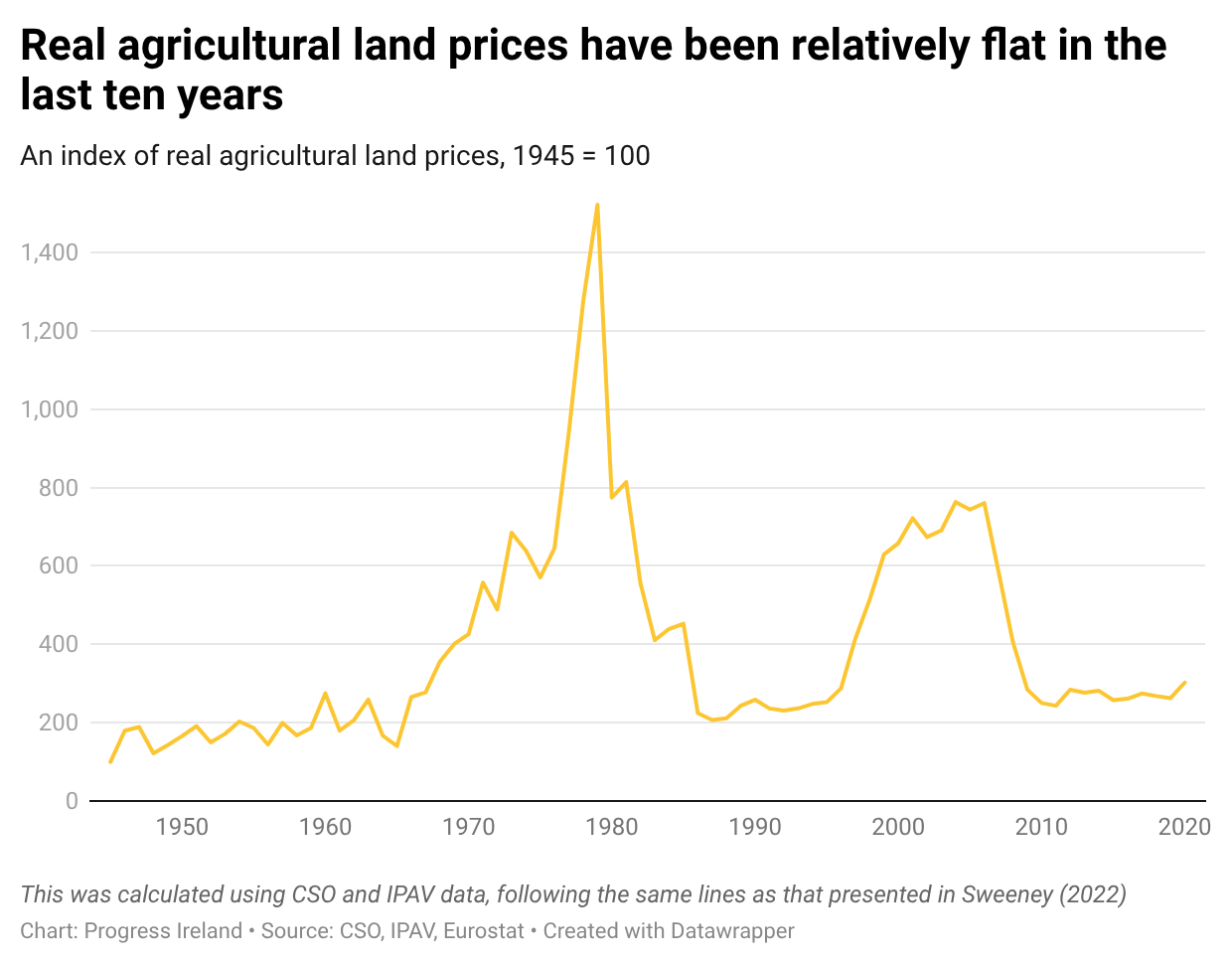

There are also agricultural land values. You would expect these to go up a lot as speculation increases. A good speculator would buy up land at low agricultural prices and hold out for a rezoning decision. As I said above, rezoning can increase the value of a plot by 8,400 per cent. This is said to have happened a lot during the boom. We should expect a surge in agricultural land prices during the boom and a fall afterwards. And this is indeed what the data shows.

Large scale speculation would see agricultural land prices rise in tow. But in real terms, agricultural land prices have been fairly flat in the past decade or so. Notable periods of inflation are easy to identify from the graph. On the one hand, we have the period of speculation that resulted in The Committee on the Price of Building Land Report, also known as the Kenny Report in 1973. On the other hand, you can see the Celtic Tiger period. But there is little evidence in agricultural prices to suggest this kind of speculation is happening en masse, as noted by this TASC report on the issue.

But what about residentially zoned land? As mentioned, there is not much data. There is a CSO page on it but year by year comparisons (as with agricultural land prices) are difficult to make. This is because the CSO is tracking transactions, not individual pieces of land.

Unactivated permissions

The last place people point to is unactivated permissions. This is where those that claim widespread hoarding for speculative gains are on a stronger footing. The claim here is that developers (read: speculators) are getting planning permission and then holding onto land, awaiting changes in planning policy or other external conditions that may make their holdings more valuable.

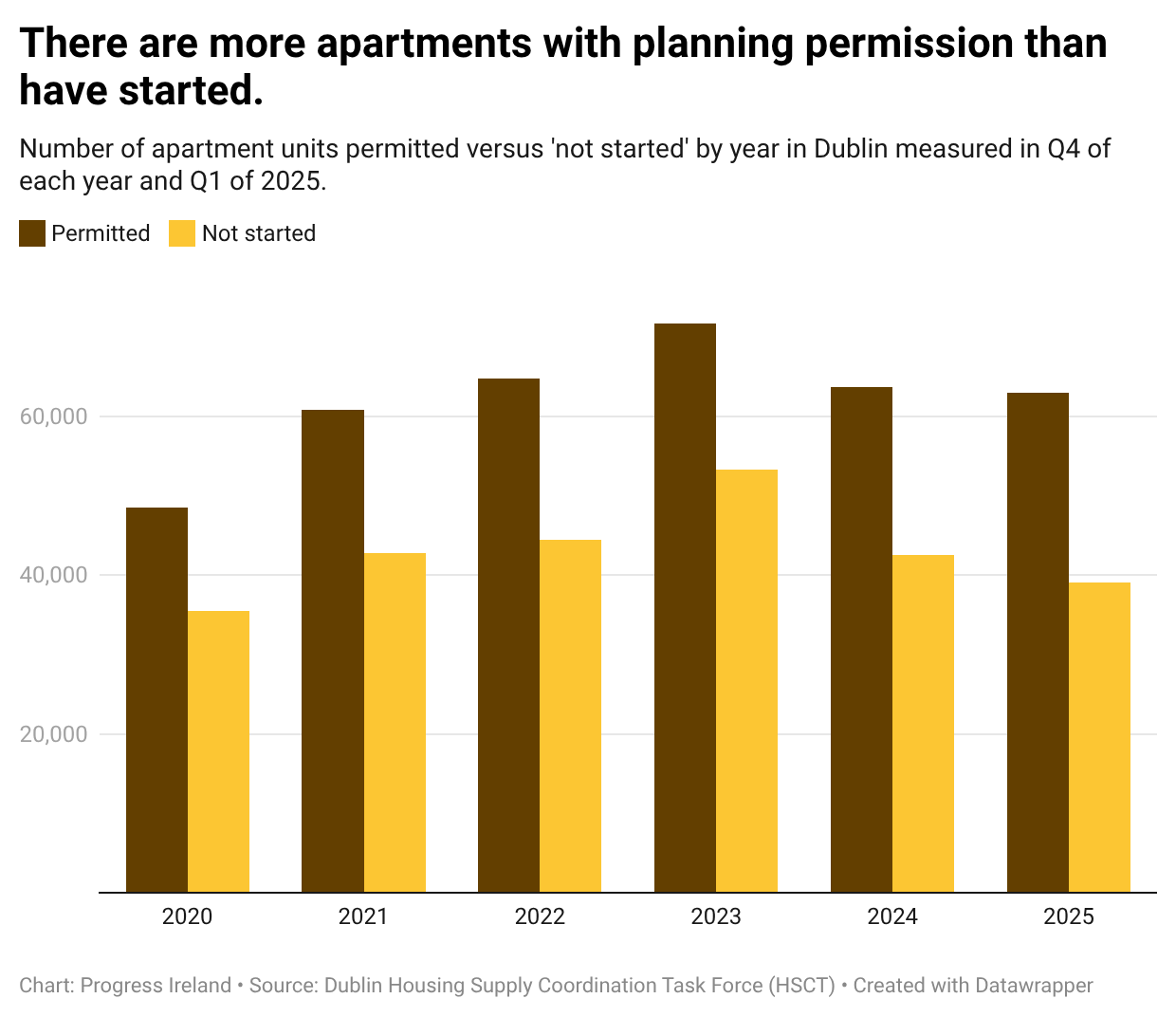

There are a lot of sites with “unactivated” permissions for apartments, especially in Dublin. The figure in Dublin has been hovering around 40 to 50,000 “unactivated” units for the last five or so years.

It is true that unactivated permissions are a major problem. But why are so many unactivated?

The first diagnosis, as mentioned, is that developers are holding out. There are lots of reasons why a developer may not build-out a permission immediately. And to be sure, holding out for higher returns is one of them. But is this the driving force behind the high numbers of unactivated permissions?

One reason for doubt comes from the fact that planning permissions are time-bound, so it doesn’t make a lot of sense to hold out for a long period of time. Under the new Planning and Development Act, permissions can last up to ten years (at the upper limit). But typically local authorities only permit five years. Permissions can be extended (as they were recently under a bespoke bill).

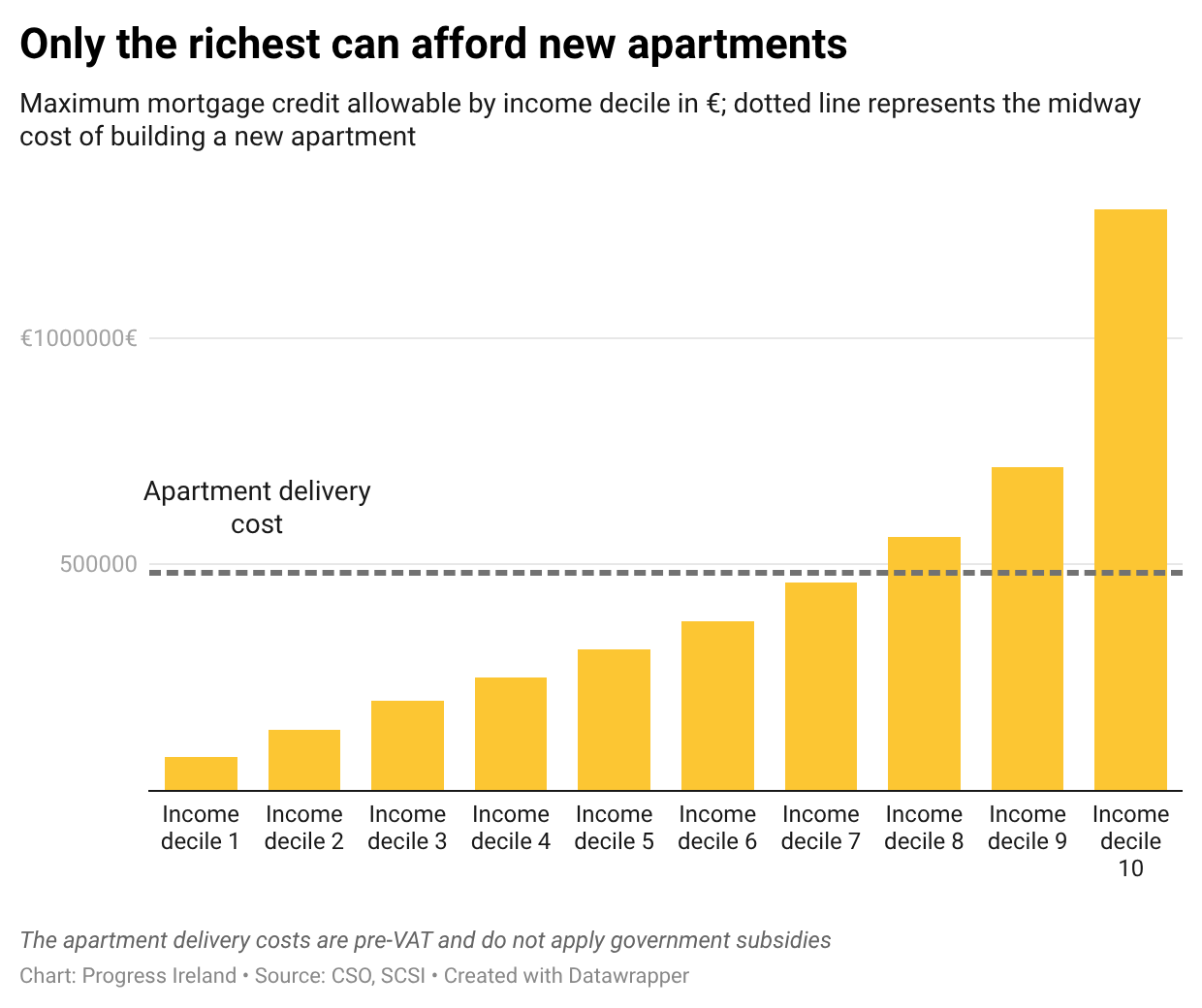

The second diagnosis is that apartments are not viable. This is the diagnosis of the government (despite one 2022 report which floated the idea, without any data, that speculation may be driving it). Viability refers to whether building can go ahead profitably. The hurdle margin – the margin required to make investment in a project worth it –is in the region of 15 per cent.

The problem is that due to high construction costs and high effective tax rates, many projects do not meet that hurdle rate of about 15 per cent.

If the market for new apartments is small due to high costs, then we should expect many projects to be stalled. That is what the data shows: a very small market for new apartments (without subsidies) and tens of thousands of apartments with permission that are not being built out.

Speculation is a red herring

I set out in this to find if there was any evidence to support the claim that hoarding and speculation is one of central, if not the main driver, of the housing shortage. I am yet to see any compelling evidence. To be sure, that does not mean the practices that fall under the phrase “speculation” don’t exist. But it does mean that, as things stand, there isn’t much evidence to support the idea.

As Matt Ygelias once said: “Nobody blames “speculators” even though it’s true that there are middlemen who make a living buying and selling used cars. And most of all, nobody blames the rapacious greed of the world’s car companies even though auto executives do enjoy the current high margins.”

Thanks Darragh! You're right that he is probably referring land banking.

In a highly constrained land market--where supply is constrained both by a lack of infrastructure capacity and by planning policy, like the NPF--land banking makes sense for any developer. We would probably see fewer homes if the big firms were to purchase land at the beginning of each project, rather than have a pipeline ready to go. There is little good data on the extent of the practice. I have never heard Sirr or anyone make a compelling case that the practice is being done in a way that counterfactually reduces overall output, so I am unconvinced that it represents a constraint.

Great post Sean.

IMO Land costs in Ireland are too high, and are driven by artificial scarcity imposed by Govt (lack of zoning, infrastructure) but are such a low overall proportion of housing costs that they don’t really matter. Even if development land was free there wouldn’t be a significant drop in the cost of housing provision, the cost of which as you know is largely driven by having the most stringent building regulations in the world, and being located on an island where we import almost every component that goes into housing construction.

Mike Bird’s book points out how Singapore avoided the ‘relative’ cost of housing spiking by maintaining freehold ownership of land, but he doesn’t point out (rightly or wrongly) that the standard of the apartments the government mandate being built there is, to put it mildly, not good. So land as a proportion of cost is much higher and therefore more impactful.

Keep up the good work!