26 policies for 2026

More of what we want, without extra spending.

Ireland has some cards to play. One advantage of Ireland is that it’s small. The benefit of being small is that it can be nimble. If the right idea makes it to the right people at the right time, it can happen quickly.

Another advantage of ours is that we’re late to the party: other rich countries got rich about a century before us. They have walked this path already. Ireland can observe how they solved problems and copy them. We don’t have to learn by trial and error.

Whatever problem Ireland faces, some other country, somewhere else, has already solved it. There’s no shortage of solutions. With a nod to Derek Thompson, a quick list of 26 policies for the New Year.

New institutions for quicker infrastructure

Organisations in general – whether private or public – have limited ability to change. They are set up to do a specific job. They can keep doing the job so long as the job doesn’t change. But when the job changes they will more than likely not be able to do the new job. In the private sector this problem is resolved by the formation of brand-new companies. In the public sector this happens much less. It should happen more often. If we want the government to take on a new challenge – like laying 146,000km of fibre through rural areas or digging 14km of metro tunnel under a city – it should spin up a new institution to do the job. Examples: Madrid’s MINTRA which built its metro system, operation Warp Speed which created a new chain of command for COVID vaccine research, NBI which laid Ireland’s broadband network (disclosure: my wife works for NBI).

Empowerment and delegation for quicker infrastructure

In the case of new public sector institutions, a lot of the benefits come from freeing projects from the civil service’s many other imperatives. Metrolink’s new setup will allow decisions to be made much faster. DARPA led to the creation of the Internet, among many other things, by giving innovators a long leash to pursue their passion projects.

Two-thirds majorities to balance individual and collective rights

Ireland struggles to balance the rights of individuals with the collective good. It’s why nationally-significant projects get stuck in limbo, why strategically important plots of land go undeveloped, and high demand areas like our city suburbs don’t add extra housing. Why don’t we sidestep the legal and political morass by creating mechanisms for balancing the rights of individuals with the greater good?

Take the problem of underdeveloped land with lots of owners. Right now, it’s hard to develop these sites because there needs to be unanimity among owners on a single plan. Land Readjustment (used to develop 30 per cent of the urban area of Japan) uses the mechanism of a double supermajority vote to resolve this problem fairly. Under land readjustment, two-thirds1 of the landowners and two-thirds of the land in question must agree to the plan. If these thresholds are met, the plan goes ahead and all land is swept up in the scheme, without requirement for CPO. Another example is Street Plan Development Zones, based on a similar law in the UK, which give suburbanites the freedom to control planning law on their own streets, subject to a supermajority vote. The idea is broadly applicable and resolves the toughest problem in development: that of achieving consent.

Grandfathering to fix Ireland’s knottiest problems (by 2035)

Lots of big problems are trivially easy to solve on paper. We’re stuck with them because their solution would be politically unpopular. A smart undergraduate economics student could draw up an efficient regime for pricing road use. It would raise money, relieve traffic, benefit the environment and grow the economy. This is a particularly urgent problem since fuel tax is in long-term decline because of electric vehicles. Nonetheless, road pricing remains rare in practice. Pricing road use takes away something to which people feel entitled. This feels unfair.

An alternative to this is to only price road use for the drivers of new vehicles. By way of compensation they could be exempted from other old-fashioned road taxes. This would raise revenue in the efficient way described above. But more importantly, it would be acceptable to voters. It would not be perceived as taking away an existing benefit. Over time, the social benefits would accrue. And by 2035 the problem would be fully solved. This idea – of grandfathering benefits to the would-be losers of a policy change – is broadly applicable. Indeed, the Irish government used it earlier this year to carve out new housing supply from existing beneficiaries of rent pressure zones.

Specific planning rules to launch a flotilla of small builders

In Ireland, developers are big. Examples would be Glenveagh, Cairn or Ballymore. Developers are also big in the UK. In the UK, about six per cent of homes per year are built by individuals. In Ireland, the number is about 16 per cent. In Germany, it’s 44 per cent and in France it’s 23 per cent. Why is there more small-scale development in Europe?

I reckon small developers are viable in places like Germany because in Germany, planning risk is much smaller. A small German builder can buy a site and know, with a high degree of certainty, what they will be allowed to build on it. That’s not the case in Ireland or the UK.

Pattern books for popular and abundant housing

Pattern books are standard drawings and specs that many builders can copy. They lower costs by removing the need to hire designers, simplifying construction, and generating economies of scale.

They also cut time and risk. When a pattern book sits inside a masterplan or is treated as pre‑approved, planning review narrows to site-specific issues, giving developers more certainty and faster starts.

Finally, they make housing nicer. By coordinating what gets built across a street, the pattern book acts as a proxy for “unified ownership,” and makes coherent, attractive places. Better aesthetics can raise public buy‑in, reducing opposition and allowing more homes to be approved and built. Much of Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian Dublin and London was built using pattern books.

Red teams to prune bad ideas

The people who come up with ideas are often not the best people to test them. This is why writers have editors. The same applies to teams and companies. To guard against blind spots and group think, some organisations establish “red teams” whose job it is to interrogate, test and attack their colleagues’ work. The ECB uses them to test for weaknesses in market infrastructure, the UK civil service uses them to critique regulations, and the US intelligence services use them to test internal analysis. Might a team be empowered to test and remove defective government processes and regulations?

Mayors to knock heads together

The state has many more agencies than before. A problem with agencies is that they’re single-minded: they care about nothing but the job they were created to do. This is a problem when differing agencies’ or departments’ goals clash. Say TII wants to build a new road, but the National Parks and Wildlife wants pristine nature. Other EU countries have stronger local governments, with meaningful power, and elected representatives to resolve these clashes. In Ireland, the only office with cross-cutting responsibility that can prioritise among competing goals is The Department of an Taoiseach.

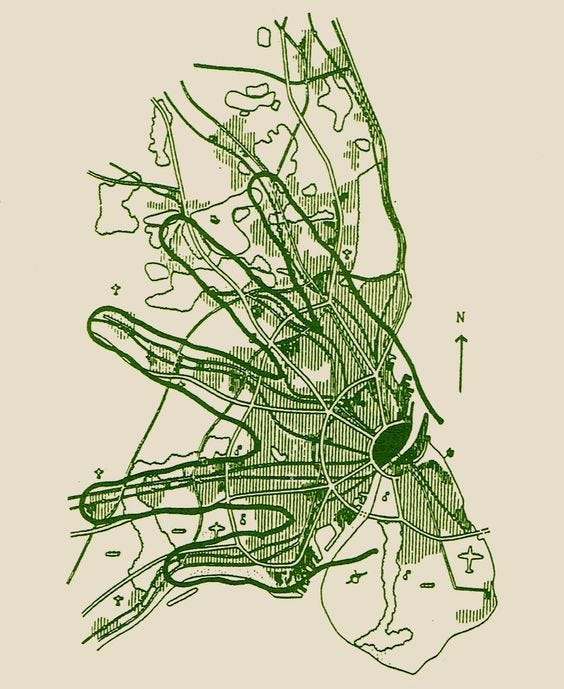

Hand-and-fingers for quality, sustainable housing at scale

Ireland needs an absurd number of new houses. The Housing Commission estimated the need is for 1.5 million new homes by 2050. That’s a new Dublin every seven years, or a new Cork every year. It’s almost seven new houses for every ten houses that exist in Ireland today. Where will they all go?

If we were to run down the list of suitable locations for Ireland’s 1.5 million homes, the top four slots would be as follows: along the DART line to Skerries; along the DART+ West Line to Maynooth; along the train line to Naas; along the rail line to Wicklow. Slot five might be the line from Cork to Mitchelstown. Galway and Limerick rail lines also have big potential. In 1947 in Copenhagen, they labelled this approach the hand-and-finger plan.

Why along the rail lines? Rail’s superpower is its capacity. A train track can move as many people in each direction as 22 lanes of motorway. Along each of the lines mentioned above, there’s enough capacity (and green space) to put between 100,000 and 200,000 homes.2 That’d make a dent in the 1.5 million.

Land readjustment to align incentives and get big neighbourhoods built

We want to accommodate all these homes in big masterplanned neighbourhoods. To make this happen, many things need to come together. Planners need to masterplan at scale and remove planning risk as much as possible. Fragmented groups of landowners need to sign up. Infrastructure providers need to lay the pipes and electrify the trains.

To bring all these elements together, we need to create the right incentives. Planners need to be incentivised to masterplan at scale, with appropriate densities. Developers need to be incentivised to put their capital at risk. Landowners need to be incentivised to sign up for the plan. Urban Development Zones, the new tool in planners’ kits, are helpful but they don’t resolve all these problems. Land readjustment is a proven mechanism that aligns everyone’s incentives so that we end up with the type of high volume, walkable, efficient neighbourhoods we need.

An Irish Rail / LDA JV to unlock 1000x increases in land value

I said Land Readjustment aligned everyone’s incentives. That’s not quite right. To build big new neighbourhoods that accommodate hundreds of thousands of people and follow the rail lines like a snake, there’s one more group that needs to be brought around: Irish Rail. Irish Rail is a key player in all this. Its investments in commuter rail can multiply the value of raw land by 100, 1000, 10,000x. This is why train companies make natural property developers.

The problem is that, at its heart, Irish Rail is a train operator and it doesn’t think in those terms. Meanwhile across the river, another arm of the Irish state is a property developer that could do a lot of good with zoned land, serviced by high capacity electrified trains.

Maybe there’s value in a joint venture between the LDA and Irish Rail? The LDA gets lots of land. Irish Rail gets customers for its trains that justify ambitious capital expenditures, and cash from sales of some existing land. The JV structure aligns their incentives so that nobody is being asked to pull on the green jersey.

Variety to maximise the usefulness of our housing stock

All can agree Ireland needs more housing. But more than that, Ireland needs more variety in housing. Ireland has lots of three bed suburban family homes, but very few small homes, homes in the urban centres, student accommodation, hotels, apartments, garden homes or retirement villages. Variety is good in itself because it lets people match with the type of home they want. A person might grow up in a three bed, move to student accommodation, stay in a hotel for a week in August, move to a rented seomra, move to a rented city centre apartment, buy a three bed, downsize to an apartment, and move to a retirement village. Policies such as broader minimum standards for apartments or street votes are about introducing variety as much as they are about introducing volume.

Higher incomes through agglomeration

It’s good to have a good transport system so people can move around more efficiently and not have their head wrecked by commuting. But there’s another big benefit of density and efficient transport: having more people near to you, within the commutable range of where you are, increases incomes through the magic of agglomeration. A reasonable estimate is that doubling the number of people within commutable distance in a city like Dublin might increase productivity by about €15,000. Another good reason to electrify train lines and use land better.

More transport capacity for agglomeration

The standard objection to building a new road or bridge is that building it won’t, in fact, reduce congestion, because of induced demand. Induced demand refers to how additional traffic shows up over time and fills up all available road space. To this I say: yes, it’s true that building a new bridge or road might not speed up the flow of traffic. But the thing that matters for agglomeration is not the speed of traffic but its volume. More people riding trains and buses and driving on roads is a good thing in itself.

Electrified rail to boost transport capacity

One easy way to boost transport capacity is to electrify more rail. Ireland has the lowest proportion of its rail electrified in the EU. Electrified rail is good for capacity, and capacity is the thing we care about if we want agglomeration and abundant housing. Electrified trains accelerate and decelerate faster, so more of them can be packed onto a line. They can also go both forwards and backwards, so they don’t need to be turned around / don’t need engines on both ends. They’re also quieter and more energy efficient.

Simplification to better grow, build and defend the EU

The EU is on a simplification kick. It’s looking at EU rules and processes it can simplify to make it easier to build, grow and defend the EU. The simplification drive overlaps with Ireland’s Presidency of the Council. It’s an opportunity for Europe and Ireland.

SMRs for clean firm power in the 2030s

Nuclear power has always been a difficult fit for Ireland. The reactors are huge and costly. They make more sense for bigger countries. Things are changing though.

Globally there’s greater openness to nuclear power, after three decades in which it was very unpopular. There’s a greater appreciation for nuclear’s green credentials. There’s a greater appreciation for the need for firm power, in a system increasingly dominated by renewables. And small modular reactor technology offers the promise of nuclear power at an appropriate scale and price point for Ireland within fifteen years or so.

The hope is that factory-built modular reactors can, over time, lower the cost of nuclear power. When the reactors are ready, Ireland should be too.

Model local area development plans for more harmonious planning

In the US as in Ireland, planning rules are set locally. In the US, the Federal Government is getting in on the act to a greater degree than previously. The US Congress has just passed the ROAD to Housing Act, which is intended to accelerate homebuilding. One idea in the act is for the Federal Government to provide template planning codes that localities are free to adapt, if they wish to encourage gently sustainable building in their area.

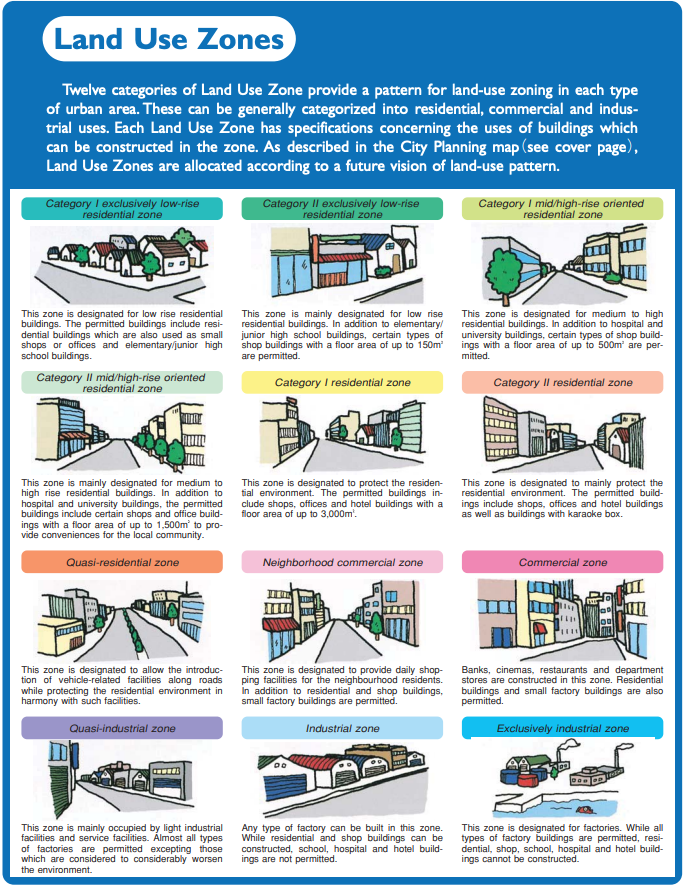

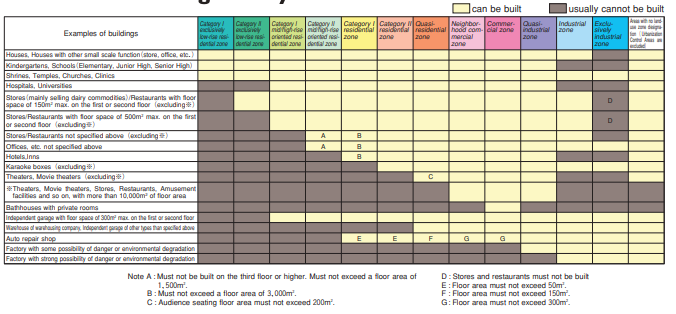

Nationally sanctioned zoning for simpler planning and more building

Ireland’s local authorities zone land to determine what can and cannot be built. There are 31 local authorities. According to Myplan.ie, between the 31 local authorities there are a total of 51 zoning types. For a country of Ireland’s size, this is a big number of zoning types. Japan is a country of 124 million people. It has 13 standardised zoning types. They are set by the central government in Tokyo. Local governments are free to implement these zoning types as they see fit. But they must stick to the zones. This impedes local governments from weaponising their zoning systems to stop building – something that has been known to happen in other places.3

Hierarchical zoning for mixed-use urbanism and more housing

Japanese zoning system has another quirk. Its 13 zones are ranked in order of nuisance, from light residential, to dense residential, to light commerical, all the way to heavy industry. Developments that are higher in nuisance value — like say light industrial — are not allowed in places zoned for lower nuisance value, like commercial or residential. But the opposite doesn’t hold: it’s permitted to build housing in an area zoned for industry.4 The thinking is that nobody is put out if they choose to buy a home in an area with shops, offices or light industry nearby.5

This rule has the effect of creating pleasing mixed-use neighbourhoods, and allowing housing wherever people wish to live.

Upward extensions to relieve housing pressure

In South Tottenham, London, there is a large orthodox Jewish community. Their family sizes are bigger than average. They value proximity to each other. And the housing stock in South Tottenham, like much of London, is made up of pokey terraced homes. To relieve the pressure on their family homes, the Jewish community in South Tottenham lobbied the council for a change to local planning rules that would allow them to add a one-story vertical extensions in keeping with the style of the area.

How many families in Ireland would avail of the chance to add a floor to their home? Might one-story vertical extensions, in keeping with the existing style of the property, be made exempt from planning permission, like kitchen extensions?

Street Pension Zones

Progress Ireland frames Street Plan Development Zones as a way to gently densify suburbs and get more housing built. There is another angle. A homeowner on an SPDZ street could use the new plan to fund their retirement. They could, for example, replace their three-bed semi-d with a duplex. They could move into the duplex’s ground floor unit and sell the first and second floor unit to fund their retirement.

Pre-commitment to stop novel projects going haywire

Government organisations are like people. They have impulses. They want things. Often, their impulses are contrary to the needs of the state. The solution is pre-commitment: “Before a government decides, for example, what kind of concrete to use, it should decide on the right processes for making these decisions. It should pre-commit to good decision-making frameworks.”

More zoned land for faster, cheaper building

One of the many problems with our housing system is that construction companies productivity is poor and it isn’t growing. Economists Glaeser et al put the blame on planning laws that keep building firms small: “Regulation keeps projects small, and small projects mean small firms, and small firms invest less in technology then productivity growth will decline". Maybe a bonus effect of more zoned land would be bigger, more productive builders?

The professor’s privilege to incentivise spin-outs

Ireland is highly exposed to US multinationals. That’s not a safe place to be. We want domestic firms to step up to the plate. How to cultivate indigenous high tech export jobs? Professor’s privilege changes the ownership of academic ideas to incentivise more startups. Right now, IP from academic inventions is assigned to the university. Giving it to professors incentivises them to spin out valuable ideas. It also reduces delay by avoiding negotiation with a technology-transfer office and university committees. Empirically, we see places that grant IP to academics have faster commercialisation, more startups, and larger knowledge spillovers.

Metascience to maximise ideas per euro

In the same vein: Ireland has a relatively puny budget for funding science. It needs to allocate this funding wisely. One wise thing do to is to create a small, full-time “metascience unit” inside Research Ireland. Metascience is about using scientific rigour to understand how to fund and manage the practice of scientific research.

Or three quarters, or four fifths. Whatever it is.

Some tunnelling required.

To be sure, there is more to Japanese zoning than the 12 zones depicted. But this simple system provides the basis for limited elaboration.

As the graphic shows, there are some exceptions. You can’t built a bungalow beside a lead smelting factory.

The Irish zoning system is flexible too, in that it allows residential in some other zones. The difference is that a) the Japanese system has much less discretion, so building is allowed by-right and b) the Japanese system allows building in light industrial zones, where Ireland does not.

We might be able to make progress on rail using new light rail cars that are battery powered. This is easier to deploy than traditional electric trains with heavier rolling stock that also require the line itself to be electrified.

Ireland really needs to double down on master planning. Local authorities must have the resources for this. The OPR’s submission on the Broombridge-Hamilton (🙄) site is quite critical of DCC’s minimalism in master planning the site. This article is good, but it is rather light on the need to devolve power and resources to local authorities. In this, Ireland is an absolute outlier for the worst. It should be far more on the agenda.