Ireland’s poor water infrastructure puts a hard cap on national growth

How Ireland’s water network places a cap on its development

The Ancient Romans built a 90 km aqueduct between 144 and 140 BC. In 1913, the opening of the 375 km Los Angeles Aqueduct after six years of construction was cheered on by a crowd of 40,000 people. But in modern day Ireland, we haven’t built a new water source for Dublin since the Poulaphouca Reservoir, which opened in 1940.

Today in Ireland, the delivery of new homes is being delayed by Ireland's inability to build, of all things, pipes. In order to get a planning permission to build housing, developers must obtain an opinion from Uisce Éireann that it is feasible to connect the new development to water infrastructure.

It is currently not feasible to connect all of the homes we need to build. According to the Banking and Payments Federation, Uisce Éireann only has the capacity to connect 35,000 new homes a year because their funding was tied to meeting the government’s Housing for All targets. The government’s 2025 housing delivery target is about 50,000.

Delays are not even the worst problem. Developers must also get evidence from Uisce Éireann that the network has the capacity to accommodate the new homes. While delays in connecting developments to the network may be fixed through greater levels of coordination and prioritisation, the capacity of the network is not so easily fixed.

There is a serious risk that Dublin’s – and therefore Ireland’s – growth will be halted by insufficient water infrastructure. Developers must seek Uisce Éireann’s (UÉ) view, as part of the planning process, as to whether the water system has the capacity for a new housing development. According to the courts, UÉ can make trade-offs – for example, about how many “overflow” incidents are acceptable – but there will come a point when water supply and wastewater plants are at their limit. When that point comes, we will see planning permissions being refused due to lack of water and wastewater capacity. And it is arguable that that point has already been reached in the case of wastewater: Dublin’s Ringsend treatment plant is now, according to the chair of Uisce Éireann, at its limit (though ongoing work will buy time by improving capacity by 15 per cent).

If Ireland doesn’t rapidly improve the capacity of the Eastern region's water network, it will threaten the economic and environmental future of the country. This is because Ireland’s most economically important city, Dublin, won’t be able to grow without more water. No water capacity means no business growth and no new housing. As one industry figure put it: no cranes without drains.

This cap will be more difficult to remove than others. I have written about the ‘cap’ on Dublin in the National Planning Framework (NPF). That cap works by suppressing Housing Supply Targets in the East of the country. The NPF’s cap is a policy choice and could be removed overnight. But Ireland’s inability to secure the East’s supply of water places a much more stringent ‘cap’ on the Greater Dublin Area (GDA) of its own.

Official estimates are likely understating the problem. As part of a plan to supply water to the GDA from the river Shannon, Uisce Éireann (then Irish Water) carried out a review of demand in 2015. Using 2011 census data and some assumptions about growth rates, they found that the GDA has been outpacing sustainable production levels since at least the early 2010s.

In this graph, the bottom line labelled ‘sustainable production’ was taken from the Water Supply Project Midlands and Eastern Region Water Demand Review published in 2015. It maps out the sustainable production levels of the water network, that is, the volume of water that can be reliably and safely supplied using existing infrastructure and water sources. As you can see, that level has already been exceeded.

The line right above that is Uisce Éireann’s initial demand assessment in millions of litres. That estimate was created in 2015 and used 2011 census data. It combines domestic and non-domestic demand and estimates the overall water demand for the region.

Above that, are two rough estimates of demand using more recent figures. The initial demand estimate contained in Uisce Éireann’s report is outdated because the population has grown a lot faster than anticipated.

The first of the two estimates uses population figures contained in the most recent National Planning Framework (NPF) that seeks to see a population of roughly 3,000,000 people in the GDA by 2040. Above that is a ‘high growth’ scenario provided by the ESRI.

When these updated population growth assumptions are translated into water demand, you can see that the GDA is outpacing sustainable production capacity much faster than originally thought.

Despite being so stark, the estimates contained in the graph underestimate water demand in at least three ways.

First, they likely underestimate population growth in the GDA. The NPF figures used in the calculation assumed a growth rate in the GDA of just 0.89 per cent per annum. In the ESRI high migration scenario, the assumption was an average growth rate of 1.2 per cent. However, between 2016 and 2022, the actual growth rate in the Eastern and Midlands region was 1.6 per cent. So, the above graph is likely underestimating population growth.

Second, the new estimates exclude commercial demand. The original report estimated both domestic and non-domestic growth and translated these assumptions into water demand. The above graph just uses population growth and doesn’t include any additional demand from a growing commercial sector.

Third, they don’t include any shifts in the commercial sector toward more water-intensive uses, such as data centres. If these were included, estimated demand would be much higher.

The Water Forum, a statutory stakeholder group, has expressed the same concern that Uisce Éireann’s original estimate is now out of date. They said:

Uisce Éireann in its calculations of the SDB in the Greater Dublin Area (GDA), has projected that the domestic demand will increase by 23% between 2020 and 2050 due to population growth in the region (average 0.8% increase per year). This calculation is based on the 2016 Census Data. However, the Forum has concerns that the deficit of supply has been underestimated for the region as the 2022 Census data has revealed a population increase of 9% between 2016 and 2022, averaging 1.5% per year over 6 years nationally.

While the estimates presented in the graph are purely for illustrative purposes, they point to the severity of the shortage. Given the growing shortage, what is being done?

The Water Supply Project and Greater Dublin Drainage Project

One of the most important projects addressing this problem is the Water Supply Project (WSP). The plan is to connect part of the River Shannon at the Parteen Basin (created as part of the famous Shannon Hyrdro-Electric Scheme in the 1920s) to the GDA.

The project is needed for at least two reasons. I have already discussed one: how the water shortage is halting and will halt the GDA’s growth. The other is security of supply.

Dublin’s water supply is unsustainably over-concentrated on a single source: 85 per cent of the GDA’s water comes from the River Liffey. This level of abstraction may prove to be environmentally damaging if rain levels reduce due to climate change.

One half-century old pipe from Ballymore Eustace water treatment plant (which processes water from the Poulaphouca Reservoir) supplies water to nearly 900,000 people, about 40 per cent of the GDA population. According to the chair of Uisce Éireann, that one pipe could “blow up in the morning.”

The need for a new water supply source for the GDA was first identified in 1996. Almost 30 years ago. However, WSP has not yet entered planning and at the current pace will not be completed at least for another decade.

The WSP was not allowed to enter planning until updated water abstraction legislation was passed because previous legislation was out of sync with European Directives. Now that that is done, WSP will soon enter planning.

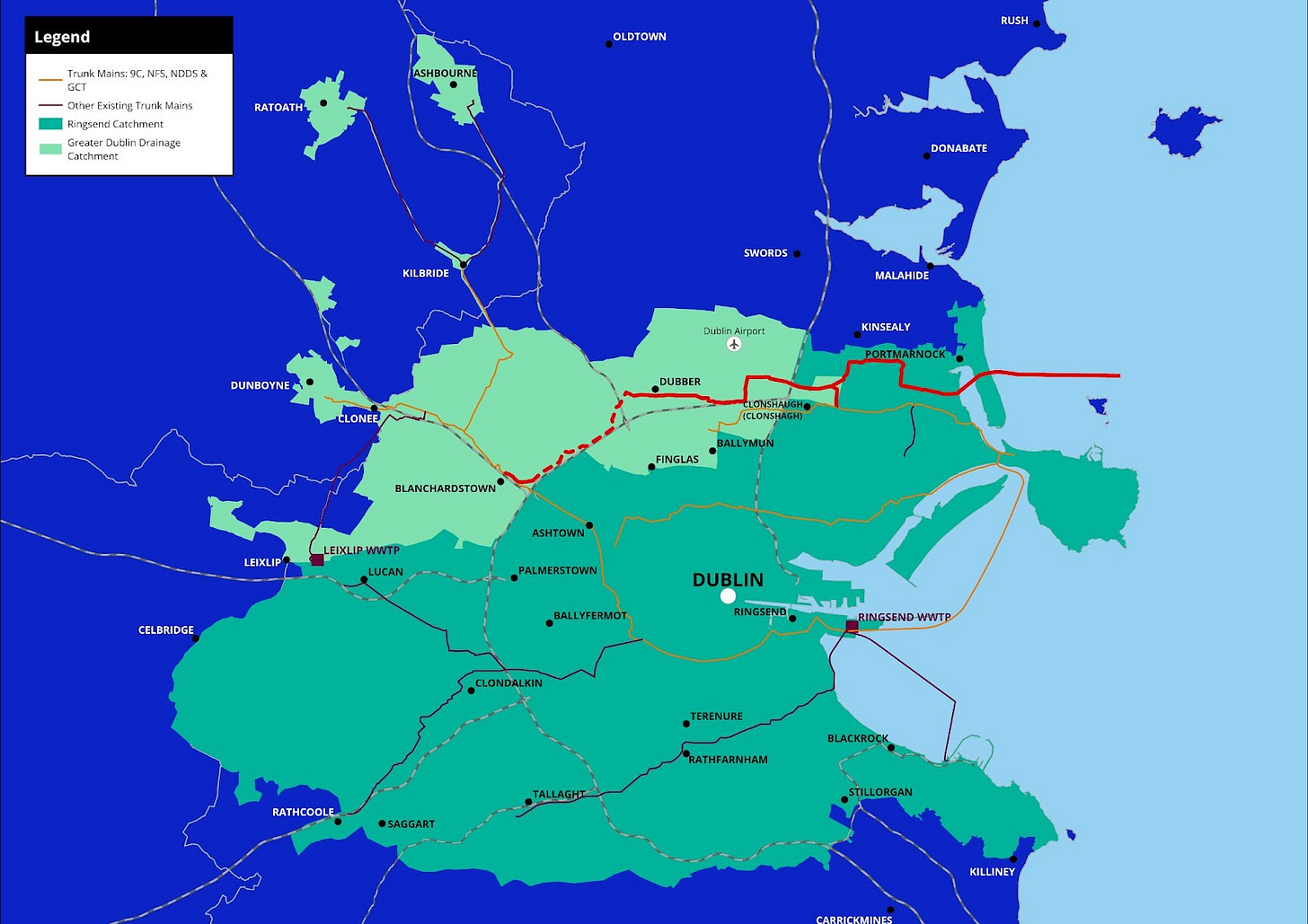

But there are reasons to think that getting WSP planning permission will be difficult. A similarly important project by Uisce Éireann, the Greater Dublin Drainage Project (GDD), has been held up for years in planning.

The GDD will provide a new regional wastewater treatment facility to serve the Greater Dublin Area. As mentioned, the Ringsend plant, which treats 40 per cent of the country's wastewater, is currently operating at overcapacity.

By 2028, without the GDD, Uisce Éireann will be unable to grant new connections to the wastewater network in major parts of the Greater Dublin Area.

The need for the GDD has been discussed since 2005. It obtained planning permission in 2019. That permission was quashed by the courts in a judicial review case in 2020. The courts decided that An Bord Pleanála failed to comply with Article 44 of the Waste Water Discharge (Authorisation) Regulations 2007. That article compels the authority to seek the observations of the Environmental Protection Agency on the likely impact of the proposed development.

While a new decision on the GDD is due soon, the delay has ballooned the cost of the project. The cost of delivering the GDD has roughly doubled to approximately €1.3 billion.

The WSP is estimated to cost €4-€6 billion. The Secretary General of the Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage noted that it could cost up to €10.4 billion, once high levels of delays and redesigns are priced in.

How we used to do it

It is easy to think that delays and cost overruns are inevitable features of modern life. But they don’t have to be and they weren’t always there.

The Shannon Hydroelectric Scheme at Ardnacrusha was built in about four years. It cost about 20 per cent of the state’s entire budget at the time. 4,000 Irish and 1,000 German workers worked on it. Upon completion, it could generate 80 per cent of Ireland’s electricity needs. But how did such a massive project get through the planning process?

The answer is it didn’t. The elected government did not have to ask for permission from other parts of the government to build important infrastructure. The plant was permitted, despite some controversy, by the Shannon Electricity Act, 1925.

Later projects, such as the Poulaphouca Reservoir were similarly permitted by an act of the Oireachtas with the Liffey Reservoir Act of 1936.

Since the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act 1963, major projects have been more commonly consented through Ministerial orders which are enabled by Acts of the Oireachtas. For example, 1974 and 1993 Roads Acts enabled Ministers to permit the construction of new roads. The Transport (Dublin Light Rail) Act 1996 allowed the Minister for Transport to give a “light-railway order” which was used to create the LUAS lines. However that power was handed over to An Bord Pleanála in 2001 with the Transport (Railway Infrastructure) Act.

Returning to the practice of using acts of the Oireachtas for major infrastructure projects is not a new idea. The former Attorney General Michael McDowell recently argued that it can and should be done again. He asked:

Why does everything in urban planning take so very, very long? The idea of a Shannon to Dublin water main has been under consideration for 25 years. Even if it gets the go-ahead soon, best estimates for its construction are that it will take another decade to build.

How is it that a relatively simply [sic] project of that kind can take 30 years from inception to construction while Victorian railway builders could build a railway from Dublin to Cork in two years with vestigial Victorian era plant and machinery? Should we revert to legislative authority for major infrastructural projects rather than planning processes based on contested adversarial methods supervised by the courts?

As the economic and environmental future of Dublin is being weighed up in a slow planning process, we should ask ourselves whether we should return to the older model of allowing democratically elected governments to permit infrastructure rather than slower and more bureaucratic authorities.