It’s widely agreed that Ireland needs to build hundreds of thousands more homes. The parties of government touted their housebuilding pipeline during the recent election campaign, but even they admitted that there’s more to do. How can we widen this pipeline?

YIMBYs (Yes In My Backyard; supporters of more housing) often argue that planning objections restrict housing supply. However, stopping the general public from participating in the planning process isn’t a real solution. To understand why, let’s first examine third party appeals in Ireland and why we have them in the first place.

What are third party appeals?

In Ireland’s planning system, the main participants are the applicant (the person who wants to develop) or the local planning authority (the council). Third parties are everyone else. Examples include adjoining landowners and environmental organisations, and in fact anyone who formally shares their views at the early stages of planning.

The planning process starts with a development plan created by the local council. Once this is approved, new planning applications are evaluated by planners to see if they fit the plan. Third parties can make submissions about those applications. The local council then makes its decision. If the third parties who submitted are unhappy, they can appeal to An Bord Pleanála (ABP).

The grounds for third party appeal can vary: the local plan wasn’t followed, or perhaps it conflicts with national planning policy. Alternatively, maybe the environmental impact wasn’t properly evaluated. Resolving these issues is the job of ABP.

Third party appeals are different from judicial review, where the planning process is checked for mistakes. Judicial reviews are about process. For instance, maybe the public weren’t properly consulted. I’m focusing on third party appeals.

How third party appeals go wrong

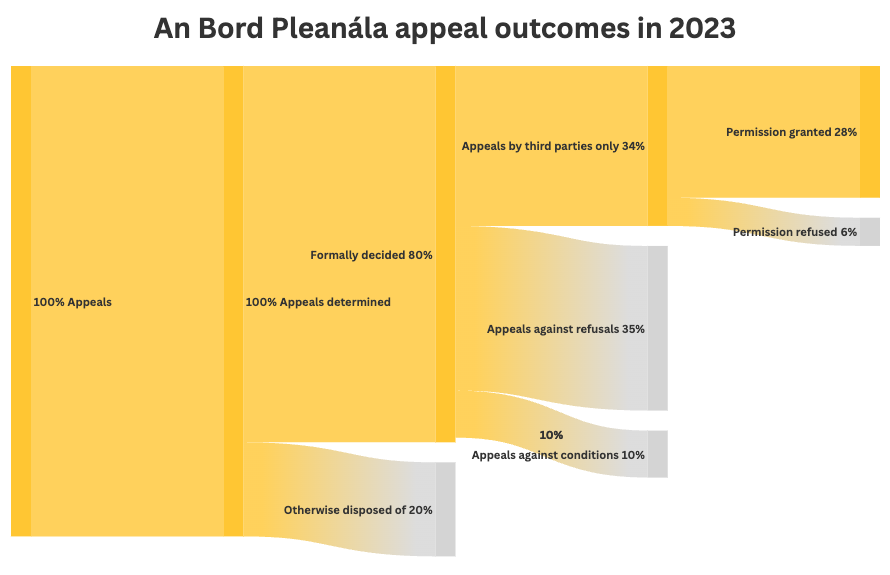

Third party appeals have a significant impact on the planning system. ABP currently has a large backlog of cases, which it’s gradually clearing. The latest figures available, for 2023, state that 43 per cent of the cases ABP formally decided on were third party appeals, ie they were deciding whether a development that has already been approved by the local authority should go ahead. What’s more, a large majority of those third party cases, planning permission was granted – in other words, the decision of local planning authorities was upheld. Those third party appeals did not change the ultimate planning outcome, but delayed it.1

The consequences of third party appeals are a large number of planning applications being examined by the country’s top planning authorities. ABP already rules on cases which go to it directly, such as strategic infrastructure projects, but third party appeals also mean it has to work out whether Leitrim council made the right decision regarding a house extension. It should be no surprise, therefore, that there’s a backlog in cases.

This process costs time and money. My colleague Seán O’Neill McPartlin recently identified delays as a key problem in the planning system because they reduce profitability:

According to the Department of Finance, a six month delay can reduce the return on a project by twenty per cent… a nine month acceleration in the planning process would be expected to improve IRR [internal rate of return] by about 2 per cent. Or, expressed differently, a nine month acceleration would be expected to boost profitability by about 25-30 per cent.

The risk of delays is a big reason why housing supply is low.

Apply third party participation at the right stage

Under a simplistic YIMBY framework, the next step seems obvious: get rid of third party appeals. However, this risks throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

There has to be a place in our planning system for third parties to share their views on development, especially if we want development to be politically durable. This isn’t about conceding every argument to people who dogmatically oppose development, but recognising the reality of politics in a democratic system: voters will eventually eject politicians who create a planning system that they don’t like.

Take Croydon, for example. Its Labour-run local council brought new planning rules allowing apartments to be built in the suburbs. Many new homes were delivered. However, these rules became the central issue during the next mayoral campaign, and the Conservative campaign opposed them. The Conservatives won and subsequently repealed them. The success story turned into a political disaster. This offers a political warning for gung-ho YIMBYs.

By contrast, it is possible to develop political support for reforms over time. The city of Houston did just that in the 1990s. At the time, developers were making lots of applications to subdivide plots of land in order to build more housing, and the city wanted to change planning laws to allow this automatically. In Croydon, densification like this prompted a backlash, but Houston allowed groups of homeowners to opt out of the new rules. A locality’s homeowners could keep their neighbourhood the same, while other areas could build more.

Opt outs took the political heat out of the issue and the planning rules remain in place today, allowing Houston to add 80,000 townhouses.

If the public supports new housing in their area, even if it’s only passive support, then it’s much less likely that a future politician is going to tear up all the rules when they reach office. However it’s achieved, public buy-in on housing makes reforms durable and gives certainty to everyone in society about what’s going to happen in the future.

There’s no way of getting around the need for public-buy in. The best way to achieve that is specificity at early stages. In other words, local plans should be as detailed as they can, and the public should be actively engaged so that they know what’s coming and can have their say. For instance, Singapore publicises its housing plans, using both digital and physical 3D models. They show how many storeys are going to be built, and what the overall density in the area will be. This is much easier to engage with than an online PDF of text and coloured maps.

Focusing public involvement at this stage means their concerns can be resolved early, creating clarity for all participants in the planning system later. There are lots of benefits to doing this.

First, in this scenario third party appeals become redundant – not because they’re outlawed, but because the public has thoroughly engaged with the plan. They now know what will be built, well in advance, because it’s been made clear to them. They’ve even seen a visual model of some kind. For instance, the Irish Cities 2070 group included detailed plans for Galway in their recent book, Irish Cities in Crisis.

That’s why Ireland’s Strategic Development Zones (being replaced with Urban Development Zones in the new Planning Act) have worked so well. They create a very specific plan for each area, following lots of public consultation – UDZs even have two consultation periods in the new act. Everyone has the chance to have their say at this early point, then the local authority can move forward together with the specific plan, creating clarity on all sides. Appeals are not permitted after this point (though judicial reviews are).

Other countries also provide excellent examples of how to do this well. For example, Singapore uses a Master Plan, renewed every 10 to 15 years, to collectively agree on how the city-state will develop. The public is engaged heavily as each plan is drafted, but after it’s finalised there are rarely any changes. There is no specific legal channel for challenges from third parties that would halt a project, as in Ireland. And nor is there a need for one – Singaporeans had their conversation about development and were able to draw a line under it, then start building.

Similarly, the Dutch planning system has traditionally been very focused on decision by consensus. Copenhagen has also had a clear city plan since 1947 which, Irish Cities in Crisis explains, can be explained by almost all Danish children – the city grows along its rail lines, spreading out from the centre like fingers.

Public involvement early would also benefit planners. As outlined above, they are spending a large amount of time, especially within ABP, adjudicating on cases that could have been settled with clearer rules and increased public involvement at earlier stages. The planning backlog could be cleared more easily. Planners provide an important service to Ireland by planning, and they shouldn’t be forced to spend so much time adjudicating.

Writing in The Irish Times earlier this year, Tony Reddy and Robin Mandal called for “robust development plans produced by local planning authorities, which set out what development will be permitted on any given site… It would remove any uncertainty and allow our planners to plan our places, rather than spending their time assessing unpredictable planning applications.”

A better way

Ireland is already moving towards a more certain planning system. A key aspect of Urban Development Zones is their specificity, which will allow planning permission to be delivered quickly. Sustainable and Compact Settlements Guidelines also provide recommendations to local authorities on medium density development, increasing clarity. Getting the public involved in local development plans will help us build a politically robust planning system and deliver the housing we need.

The ABP diagram resets percentages at each stage, but the chart below uses the same figures to show the percentage of all appeals that resulted in a given outcome.